Some Favorite Reads From 2022 14 Jan 2023 3:00 PM (2 years ago)

Another year, and another blog post (singular). Oh well. I always have aspirations to publish more! But you know, one of the joys of being semi-retired is not having to do anything. You know, it’s been a hard few years. So I tried to take it easy on myself in 2022. I spent a lot of time exploring, a lot of time reflecting, and a good bit of time just doing whatever felt right at the time.

Recently I’ve been reflecting on some of my favorite things from last year. Maybe as a way to focus on the positive. Maybe as a way to keep track of time in our time sick world. Maybe just to get back into the habit of writing. So here’s some of my favorite reads of 2022.

Books

I really enjoy reading, but this year I kind of gave myself a pass on anything too serious — mostly sticking to my trusty home base of science fiction.

Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone’s This is How You Lose the Time War

From the publisher:

Among the ashes of a dying world, an agent of the Commandment finds a letter. It reads: Burn before reading.

Thus begins an unlikely correspondence between two rival agents hellbent on securing the best possible future for their warring factions. Now, what began as a taunt, a battlefield boast, becomes something more. Something epic. Something romantic. Something that could change the past and the future.

I fucking loved this book. I started it based on a recommendation from a friend, and didn’t really look into it much before I started. This book is much less about the plot (which is a play off The End of Eternity) and more about the writing and world building. The best way I could describe it is a spy story told through love letters in a poetic universe.

Think of birds as a comms channel I can open and close seasonally; fellow operatives relate their work to me at the equinoxes; Garden blooms more brightly in my belly. There’s enough traffic that it’s a simple matter to disguise incoming and outgoing correspondence, misdirect, hide in plain sight.

It’s also a short read, which was a nice breath of fresh air after finishing off the Dune series prior to picking this one up. I have a feeling this is going to be one of my most recommended books going forward.

Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendevous with Rama

From the publisher:

An enormous cylindrical object has entered Earth’s solar system on a collision course with the sun. A team of astronauts are sent to explore the mysterious craft, which the denizens of the solar system name Rama. What they find is astonishing evidence of a civilization far more advanced than ours. They find an interior stretching over fifty kilometers; a forbidding cylindrical sea; mysterious and inaccessible buildings; and strange machine-animal hybrids, or “biots,” that inhabit the ship. But what they don’t find is an alien presence. So who–and where–are the Ramans?

I’d never read the Rama books before, so when I heard that Denis Villeneuve was going to be tackling Rendevous with Rama, I took the opportunity to read the whole series (Rendevous with Rama, Rama II, The Garden of Rama, and Rama Revealed).

Rendevous with Rama is a fantastically Clarke book. A team of highly trained professionals all work together to explore a mysterious object in space. Does much more need to be said? This book went down like a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. My only criticism is that it left me wanting for was more.

Rama is a cosmic egg, being warmed by the fires of the Sun. It may hatch at any moment.

And unfortunately, there is more.

Clarke teamed up with Gentry Lee to write three more novels — Rama II, The Garden of Rama, and Rama Revealed and I all I can say is: I do not recommend them. They are upsetting in very odd child-bride wedding night kinds of ways.

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Elder Race

From the publisher:

A junior anthropologist on a distant planet must help the locals he has sworn to study to save a planet from an unbeatable foe.

I loved Tchaikovsky’s Children of Time, so when I heard Jason Snell offer up Elder Race on The Incomperable, I decided to give it a go. I absolutely love the premise of this book. It’s a singular story told from two different viewpoints, one of them science fiction, and the other fantasy — both happening in parallel — because the two main characters don’t share enough dialect to explain themselves to each other.

They think I’m a wizard. They think I’m a fucking wizard. That’s what I am to them, some weird goblin man from another time with magic powers. And I literally do not have the language to tell them otherwise. I say, “scientist,” “scholar,” but when I speak to them, in their language, these are both cognates for “wizard.” I imagine myself standing there speaking to Lyn and saying, “I’m not a wizard; I’m a wizard, or at best a wizard.” It’s not funny.

And who doesn’t love an old, cranky wizard anthropologist?

Miles Cameron’s Artifact Space

From the publisher:

Out in the darkness of space, something is targeting the Greatships.

With their vast cargo holds and a crew that could fill a city, the Greatships are the lifeblood of human occupied space, transporting an unimaginable volume - and value - of goods from City, the greatest human orbital, all the way to Tradepoint at the other, to trade for xenoglas with an unknowable alien species.

This was another recommendation from a friend, and I’m glad I picked it up. At it’s core, it’s about highly competent people all working together, pushing their limits, and achieving success. It’s the kind of genre someone once described to me as competency porn — Star Trek: The Next Generation being the ultimate example.

There was very little drama in Space Operations. In fact, every station projected an elaborate aura of calm, as if they were competing to be dry and emotionless. No one swore, no one spat, no one was angry or afraid. Nbaro loved it.

This book pulls from a lot of familiar ideas — the Greatships are an obvious call back to Battlestars, while a lot of the socialist themes call back to Star Trek’s economy. My biggest criticism of this book is the maddening way Cameron switches back and forth between using character’s first and last names — even within the same scene! It makes it incredibly difficult to keep track of who is who with such a large cast, and toward the end I caught myself not even remembering who a certain person was.

Dennis E. Taylor’s Heaven’s River (Audiobook)

From the publisher:

More than a hundred years ago, Bender set out for the stars and was never heard from again. There has been no trace of him despite numerous searches by his clone-mates. Now Bob is determined to organize an expedition to learn Bender’s fate—whatever the cost.

The Bobiverse is probably my favorite audiobook series of all time. It’s all a part of a grand space opera spanning the galaxy… but also pretty sarcastic and silly? Ray Porter does an amazing job of narrating these books, and is a large part of why I enjoy them so much.

Heaven’s River finds a way to pull the series back from the infinite and focuses back down on a single planet for a great little beaver adventure.

Well, space beavers.

Even More Books

Neal Stephenson’s Termination Shock: Okay, I actually like Stephenson, and this is a very good book about the inevitable future of Geoengineering and it’s political consequences. Coupled with a very weird Queen fetish. It’s weird. Weird enough to take away from the story line. But if the climate angle of the book interests you — I highly recommend After Geoengineering as a follow-up.

Baoshu’s The Redemption of Time: A semi-official 4th book of the Three Body Problem. This is a great continuation of the series, and a good way to answer some lingering questions about the Trisolarians.

Frank Herbert’s Heretics of Dune (Dune 5): I was a little shocked at how much I loved this book. I mean, I love Dune. But this one ended up being one of my favorites of the series. Great new characters, new technologies, and a whole new set of powers for the Atreides genetics.

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Children of Time: This was actually a re-read in preparation of reading Children of Ruin and the upcoming Children of Memory. What can I say? It’s one of my favorite science fiction books of all time — even if only for the worldbuilding. Sentient spiders? Sentient spiders!

Newsletters

Alex Steffen’s The Snap Forward

From Discontinuity is the Job:

To be alive right now is to find ourselves flattened against the fact that the entire human world—our cities and infrastructure, our economy and education system, our farms and factories, our laws and politics—was built for a different planet.

I can’t remember exactly how I stumbled on Alex Steffen’s The Snap Forward but the idea instantly clicked with me. His newsletter focuses on how climate has affected our infrastructure, our society, and our relationship to the world. I love his newsletter because it makes me feel more sane in a world that keeps trying to sell a new carbon offset marketplace as the solution.

From Tempo, Timing, and the Translucence of the Future

The tempo of change, and our refusal to acknowledge its acceleration, has turned our visions of continuity, stability and value into fantasy worlds. We’re cosplaying people who live in past decades before discontinuity ate our societies.

I wouldn’t classify The Snap Forward as doomerism, either. It’s a focus on accepting the world as it is and looking for solutions within that framework. Even if all emissions were cut to zero tomorrow, we’d still be facing a myriad of very challenging futures. What do we do with that knowledge? How do we prepare for the transapocalyptic now?

Matt Levine’s Money Stuff

I’ve been reading Money Stuff for a few years now, and I can’t really put my thumb on why I love it so much. Sure, it’s about finance… but kind of the weird stuff in finance. More about the cogs of the machinery and the weird personalities in the news than it is about whether the S&P 500 is going to go up or down next week.

From FTX’s Balance Sheet Was Bad:

But then there is the “Hidden, poorly internally labeled ‘fiat@’ account,” with a balance of negative $8 billion. I don’t actually think that you’re supposed to subtract that number from net equity — though I do not know how this balance sheet is supposed to work! — but it doesn’t matter. If you try to calculate the equity of a balance sheet with an entry for HIDDEN POORLY INTERNALLY LABELED ACCOUNT, Microsoft Clippy will appear before you in the flesh, bloodshot and staggering, with a knife in his little paper-clip hand, saying “just what do you think you’re doing Dave?” You cannot apply ordinary arithmetic to numbers in a cell labeled “HIDDEN POORLY INTERNALLY LABELED ACCOUNT.” The result of adding or subtracting those numbers with ordinary numbers is not a number; it is prison.

It’s an understatement to say I don’t love finance, but I do enjoy me some Money Stuff.

What’s Next?

I’ve really been enjoying re-visiting some of my favorite authors and finishing off big series I never quite got around to. Last year I finally finished off the whole of Frank Herbert’s Dune (never having read 5 & 6 before), and this year I’m getting the itch to do the same for Foundation. To be frank, I don’t even remember where I ended with that series. But it does feel like a good opportunity to maybe just re-visit the entirety of the Asimov Universe… in chronological order. I’m also getting a terrible itch to revisit a bunch of Vonnegut’s work after watching the excellent Unstuck in Time. But I like new authors too!

I’m also interested in finding more books and newsletters about… I guess you’d call it urban design. Stuff like Strong Towns and other sources of how to adapt our cities into resilient communities. I actually have background in city planning from my Civil Engineering days, but I feel like there’s been a big surge in new thinking that goes farther than the YIMBY/NIMBY noise of the past decade.

Have some recommendations? Hit me up on Mastadon: @kneath@indieweb.social.

My Very Own Money Pit 29 Mar 2022 4:00 PM (3 years ago)

“So, are you gonna have a swimming pool?”

No, I am not going to build a swimming pool in South Lake Tahoe.

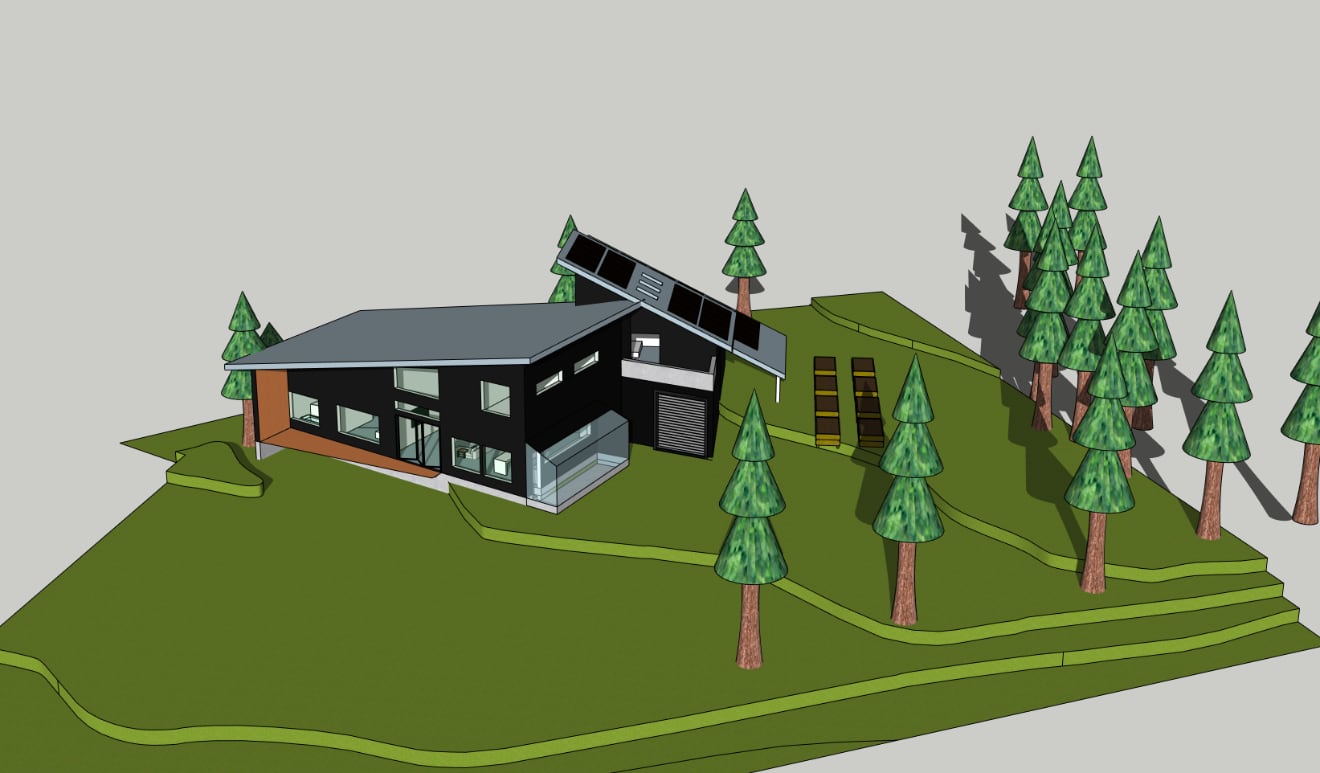

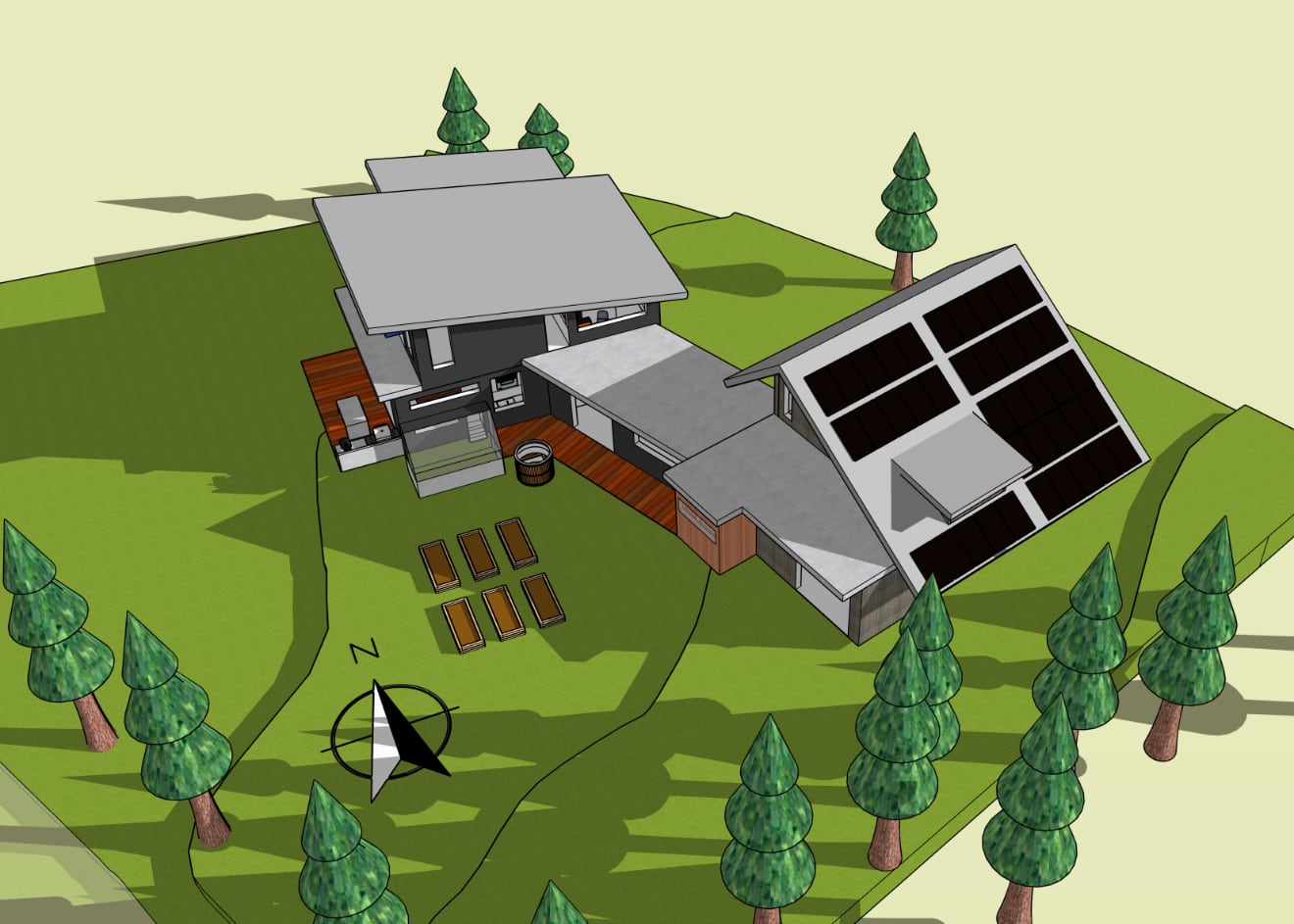

In fairness, the hole in the ground did look suspiciously swimming pool esque. But this hole in the ground was for my basement. A hard won basement that required consultants and backhoes long before any building plans existed. A basement that I’m very excited about! It’ll allow the house to sit slightly proud of the grade, rising above the snow in the winter, protecting the crawlspace from hibernating bears, and presenting a non-ignitable material to burning embers and grass in the summer. And the extra space will afford a root cellar, music room, and mechanical equipment inside the conditioned envelope — all while staying within TRPA’s coverage and height limits.

All of that is to say — I’m building a house! Which is kind of a weird turn of phrase — I won’t be building it. The good folks at Sierra Sustainable are handling that.

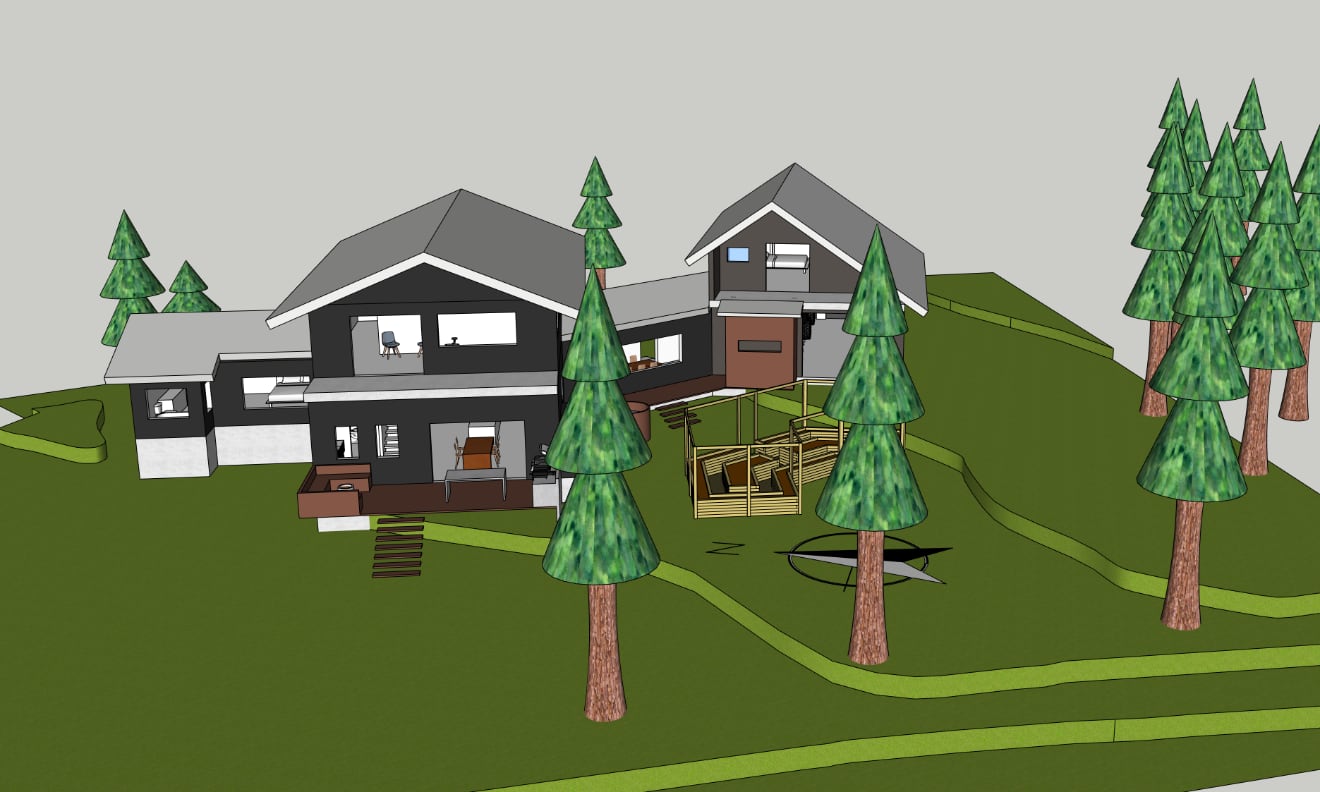

But over the past two and a half years, I’ve been absorbed in designing this house. I’ve sucked up information about architecture, building science, and local regulations — thrown them into dozens of SketchUp models — and my builders have iterated on them and turned it into a set of construction documents.

After a couple years of building department bureaucracy, a megafire burning through town, a historic atmospheric river, a month of record snowfall, and the driest winter on record… it’s starting to become a very real house. My very own money pit!

And you may ask yourself

well, how did I get here?

That house

If you spend any time in Tahoe, you’re familiar with that house. It’s the same house with slightly different siding. It pays no attention to the angle of the sun, local weather, the shape of the lot, or the positions of the trees. It is too large and expensive for almost all local working class residents. It is Tyvek-wrapped, forced-air, asphalt-shingle relic of outdated building science, unprepared for the present — let alone the future. Spec builders love it — they pour the same foundation, frame the same walls, install the same plumbing and mechanicals. It’s known. Building departments love it — what’s better than a plan that’s identical to the previous 90 incarnations? You can practically take a nap during plan check.

I hate that house.

But I have to admit it is not an evil house. It is how the vast majority of houses in America are built today. Developers buy large swaths of land, buy a couple of off-the-shelf building plans, and build the exact same house over and over, occasionally letting clients choose siding and interior finishes. It is the bleeding edge of the financialization of shelter.

So what do you do if you don’t want that house? Hire an architect!

I didn’t hire an architect

More so than a beautiful artifact of architecture, I wanted a well built home designed for Tahoe. That made my first priority to find good builders. Ones that embraced modern building science, use quality materials, are familiar with our local weather and regulations, and employ experienced craftsmen.

One day while wandering around a new neighborhood, I spotted a house that wasn’t that house. This house was Lighthaus — a single family residence designed by Peripherie Design and built by Sierra Sustainable Builders. It was the first time I’d seen builders inside the basin building something different.

Later, when touring the house during their completion party, I could see this house was built by people who care. My assumptions were validated by the designer/owner who said something like I wouldn’t even consider working with a different build team in the future. After meeting Cory & Brandon and learning about their passion for well-built homes and their love for South Lake Tahoe, I knew they were the team I wanted to work with.

After acquiring an empty lot and settling on the build team — my next move was to start the bureaucratic struggle with the building department toward a building permit. I know, this probably feels a bit backwards if you’re used to building in Idaho. But this is California — and inside of the Lake Tahoe watershed at that. At the time I closed on the lot (summer of 2019), it was looking like I wouldn’t be able to get a building allocation (roughly, permission to submit building plans) until 2022 due to a forthcoming two year audit. So it was important to start this process early.

In the meantime, I wanted to better understand the limitations and possibilities of what could be built on the lot so I could provide better feedback during design. Tahoe is a unique place to build homes, and the TRPA (Tahoe Regional Planning Association) imposes several restrictions that are unique to the basin — most notably coverage. Coverage is square foot limiting algorithm that encompasses roof overhangs, driveway size, decking material, and foundation footprints. It’s not intuitive or easy to understand, but it is the overriding design constraint for all residential construction.

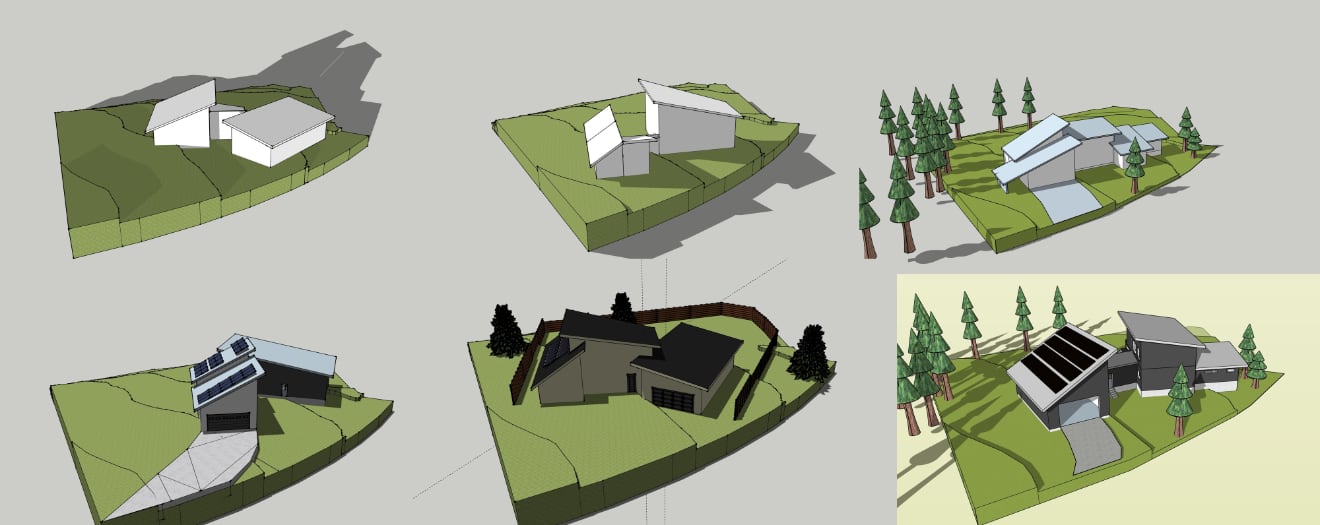

So I picked up SketchUp, watched a few tutorials, and started sketching out some ideas to explore what was possible.

As I got deeper into this process, I realized that I was really enjoying it. Modeling in SketchUp allowed me to rapidly see the tradeoffs of positioning the driveway in different areas, see how the sun would move through different rooms throughout the days and seasons, how much room I’d have for furniture, what the shape of the yard would look like, how much roof area would be available for solar panels — and all in a model with real measurements that fit within the actual restrictions for our lot.

So, that’s why I didn’t hire an architect. I just really enjoyed designing this house. Despite my civil engineering degree, I’m not anti-architect. In fact I’m working with several for other projects right now! But for this house? My house? I decided to keep doing the thing that brought me joy.

Iteration, iteration, iteration

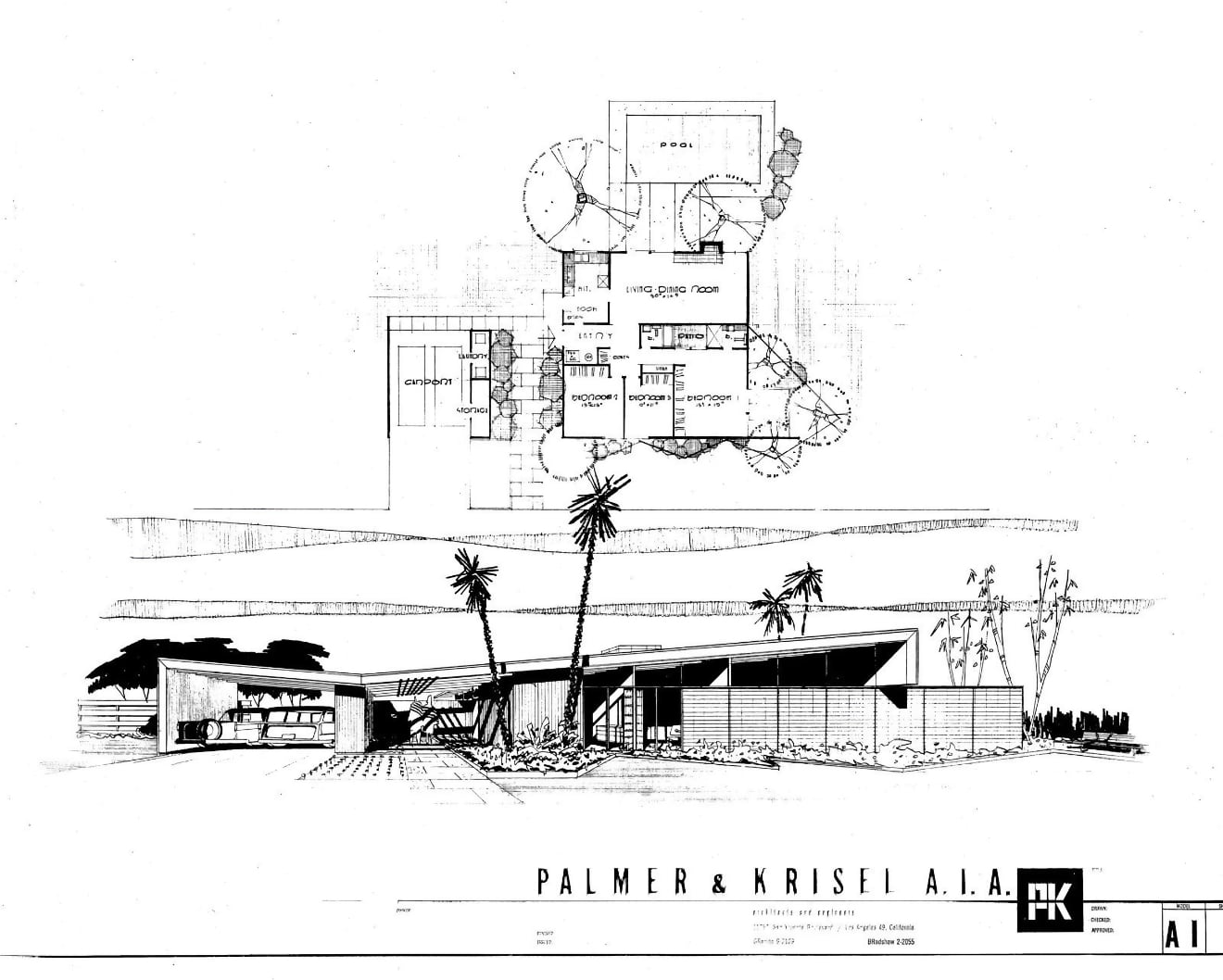

I’m a big fan of iteration when setting out to create something new. In a perfect universe, I’d build a house, live in it for a while, and re-build it every year for a decade or so. Every iteration of the house would improve upon its predecessor until all the kinks were ironed out, the light hit the walls just so, and every space was perfected for its use. But that’s a fantasy left for science-fiction. In the real world, building a house is a one-shot effort, and that means lots of planning. Every wall, every window, every doorway needs to be carefully designed and engineered long before construction starts. That’s doubly true in today’s world of long lead times (the supply chain and all that). Traditionally, architects have used sketches and drawings to communicate their ideas to their clients during this phase.

These drawings kind of suck. They’re pretty artifacts to look at, but they don’t do a good job of describing how a house will live to someone who isn’t deeply experienced in building structures from drawings. This is why architects also learn how to create physical models made of styrofoam and toothpicks to communicate their ideas.

Unfortunately, we’re not building a school for ants, and these models don’t communicate interior spaces well at all. More importantly, drawings and models aren’t really iterative. They take a long time to produce, and can’t be easily modified. But this is where computers excel! Iterations are cheap, and easy modification is the rule. This is what drew me to 3D modeling — specifically SketchUp. I have to admit I was intimidated — I had never really done any 3D modeling. But the world of 3D modeling has become extremely accessible in the past decade or so. There are many free tools (SketchUp and Blender being most popular), and tons of free training videos available. It only took a few days of dedicated study time to master the basics and start getting value out of my models.

Most importantly, the process was very iterative — I could copy and paste elements from different ideas together, rotate them around, poke windows wherever I pleased, and gain a lot of understanding for how the house would feel with minimal effort.

I love this type of accurately-modeled iteration because it allows you to play with ideas and see tradeoffs in a holistic sense. It’s like using real user data for your digital prototypes instead of nicely formatted cherry-picked sample data. What is the tradeoff of solar production, passive gain, and garden size given different building masses? How much smaller would my kitchen need to be if I were to position the driveway differently?

This is the core of why I love to use iteration on problems with several interconnected variables. You can try to be boy-genius and juggle height restrictions, setbacks, coverage, sun paths, roof pitches, and trees in your head… or you can just try a dozen different ideas and build an intuitive model of the problem over time.

Curious if a solution will work? Try it out.

You don’t even have to be very experienced in SketchUp to get a lot of value out of it. Just having a realistic geo-located sun model is an incredible tool for building houses. Ever wonder how light will move through your open concept living room during the summer solstice? Easy!

In the end, the majority of my time in SketchUp has been used to virtually wander around my house-to-be. To look at the kitchen from different angles, to play with different appliance sizes, and to think about how we’ll live in the space. I’ve definitely become that person wandering around my friend’s houses with a tape measure to better match reality how my 3D model feels. Oh is that island 12ft long? Interesting.

All this casual wandering and time spent with the construction documents has also given me an accidental bonus — I will know this house. I will know where every air duct is, how the floor is built, where the electrical wires go, and why every wall is where it is. As someone who has spent his whole life solving mysteries of old houses, it’ll be kind of nice to live in something that isn’t a mystery.

And yes, if you so choose there are many ways to import your SketchUp models into VR headsets and even-more-virtually wander around your house to be.

Collaboration

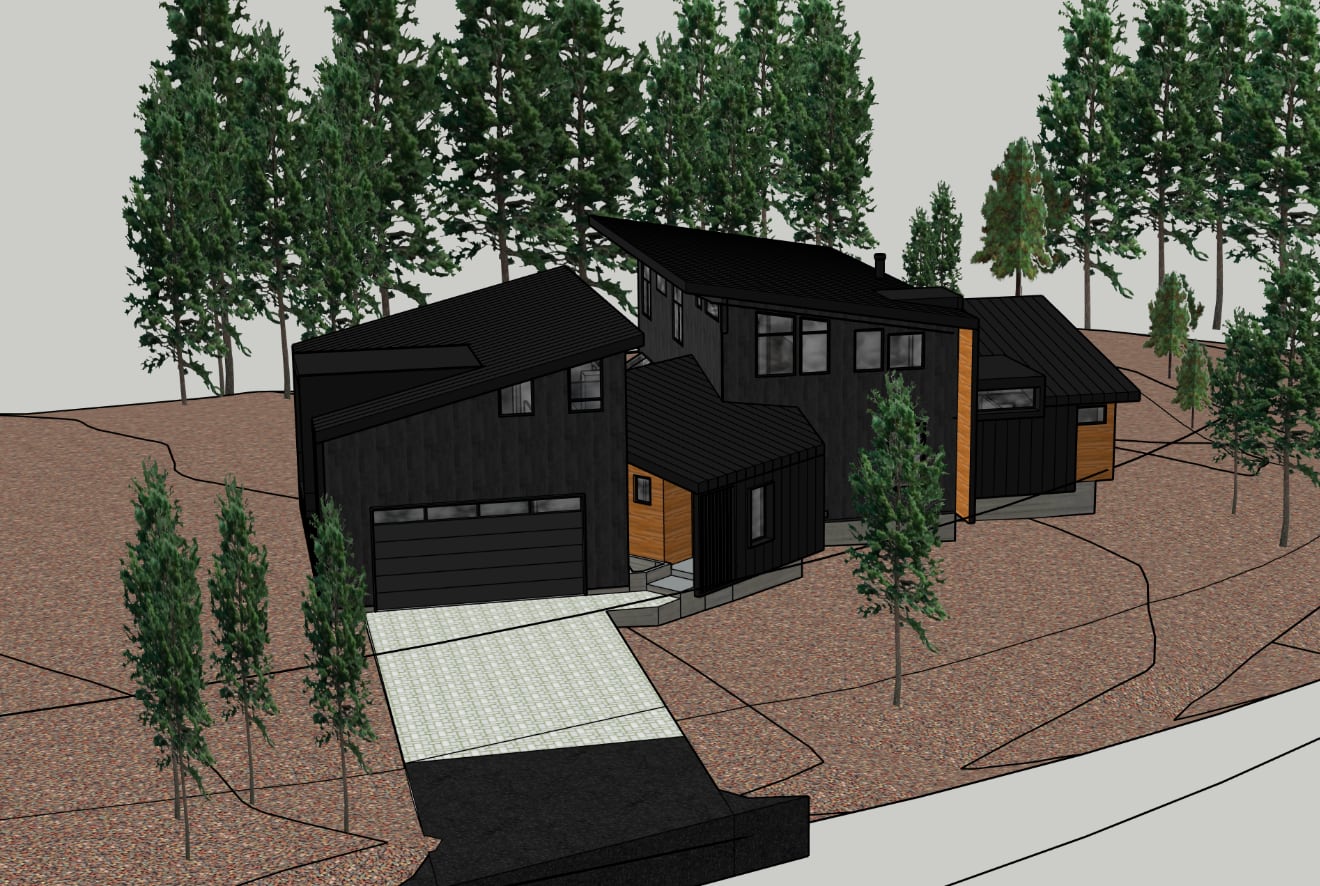

Another huge benefit of iterative tools like software is the collaboration it brings possible. Which was pretty important. Because I am no architect, and I have never designed a house. So it was good to have Brandon from SSB take my models and make something a little more reasonable and buildable.

Because I’d taken the time to learn SketchUp, I could then take his models and iterate on them the same way he’d iterated on mine. And — honestly — this kind of feels like how designing a house should work.

The one-way street of iteration via design reviews feels very outdated now that I’ve worked this way. An architect may be an expert in how to design buildings — but you’ll be living in this house, not the architect. You’ll be able to build a better mental model of how you expect to live in it.

Beyond SketchUp

At this point, the construction documents are done, the foundation has been poured, the windows have been ordered, and the framers are assembling large piles of engineered lumber into a permanent structure. The floor plan won’t be changing.

So my interests have shifted from SketchUp toward more realistic renders to explore materials and lighting. And hoo-boy is there a deep end to fall down that rabbit hole.

The particular deep end I’ve decided to settle on is v•ray. And for as frustrating as rendering can be, the results can sure be pleasing.

With every render, I get a little bit better at understanding what kind of textures provide a result similar to my real-world samples, and just how much detail is needed to really pull off an accurate render.

And I think that pleasing nature is what has kept me busy. Because if I’m honest, at this point I don’t think the renders are helping me that much. I’ve learned through trial and error that rendering is a lot more of an art than a science — so in a lot of ways I’m making pretty pictures, not accurate views of what will be.

All in all, this has been an incredibly fun project to work on. And it’s even more exciting now that the building is starting to take shape in the physical world. Even though I spent five years of college learning to design physical infrastructure, my professional career has revolved around building things in the digital world. And that was fun! But deep in my heart I’ve always been pulled towards building things in the real world — bridges, buildings, roads, and the like. The accessibility of 3D modeling has really helped bridge the gap of speed of iteration (what I loved about working in software) and the realness of physical infrastructure (what I loved about civil engineering).

I’ve also enjoyed the process of getting here. Aside from 3D modeling, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to understand what makes a good home a good home. I’ve learned about a form of architecture that deeply resonates with me, and just how far building science has come in the past few decades.

For better and for worse, this home will be a product of my dreams, born out of my opinions of where our future is headed. It’ll be a bit ridiculous, but in ways that might be confusing to most. I won’t have a 10,000 sqft deck overlooking the lake, but I will have a geothermal heat pump heating the hot tub and windows with excellent air sealing. In fact — the stuff I’m most excited about isn’t how the house looks at all, but rather the way the house will live. How the snow sheds. Why it’ll resist ice dams. How it’ll deal with smoke season. How it’ll resist grid failures. And why, for the first time in my life, my house will have straight walls.

You can be an architect house designer!

If you’re building a commercial building or multi-family residence, you need an architect — someone with a state issued license that allows them to call themselves an architect. Anyone without that license is just a designer. However, I suspect a lot of people don’t realize that anyone can be a designer. In every state in America it’s entirely possible to design your own home without any kind of licenses or certifications. It may go without saying, but your home still has to be engineered and meet all building codes and regulations. And of course — you need to be able to afford it. Half an architect’s job is budgeting.

And well-built modern homes are complicated. Long past are the days of craftsman homes ordered at Sears and delivered as a pile of lumber on a truck. If you’re building a house today, you’ll want a small army of consultants to help you in your quest.

So while it’s fun to say I designed this house, in reality there is a huge team of people who took my ideas and made them real. The geotechnical consultant to prove the basement, the structural engineer to design the structural members, the MEP (Mechanical, Electrical, Plumbing) consultant to design the fresh air & HVAC systems, the solar firm to design the solar & storage systems, the cabinetry firm to design the kitchen, the low voltage consultant for ethernet drops, the drafting firm to create the construction documents, and of course — Brandon at Sierra Sustainable who wrangled all of these people and leveraged his extensive experience in building homes to transform my ideas from a concept into a comfortable, buildable, efficient house that meets code.

This house has been the top of my mind for a long time now, and I’m hoping to write more about how I’ve been thinking about it. I’ve long been frustrated with the shoddy houses built by recent generations — houses that are already falling apart and fail to inspire. But more importantly — our climate is changing — and our shelter is in desperate need of catching up. Floods, fires, thick smoke, extreme heat, ice storms, downpours, utility outages, and more — these are all going to be a regular part of our modern lives. We can’t rely on “typical” conditions going forward.

Building technology (both old and new) has answers to many of these challenges, and it doesn’t necessarily mean living in an underground bunker. Our homes can be resilient and comfortable if we so choose.

Net Zero Ish 29 Nov 2021 3:00 PM (3 years ago)

On the one hand, Earth is rapidly becoming uninhabitable for humans as a result of human-caused climate change. On the other hand, it’s pretty easy to ignore the cascading disaster most days. Climate change isn’t really a personal thing for most of us, especially if you live in North America or Western Europe. Sure — we have more wildfires, more droughts, more hurricanes, more floods, and a sort of ominous feeling of dread hanging over our heads — but it’s honestly not that big of a deal to crank up the air conditioner and book a flight to somewhere more comfortable.

But… what if you didn’t want to ignore it? What if you wanted to leave the world a better place carbon-wise than when you found it? You can’t do that with lifestyle changes unless you cease to exist. That’s why we talk about net zero approaches to carbon footprints — purchasing carbon offsets to balance out our emissions.

It’s a wonderfully simple idea.

Committing to net zero by purchasing carbon offsets is very easy and relatively cheap!

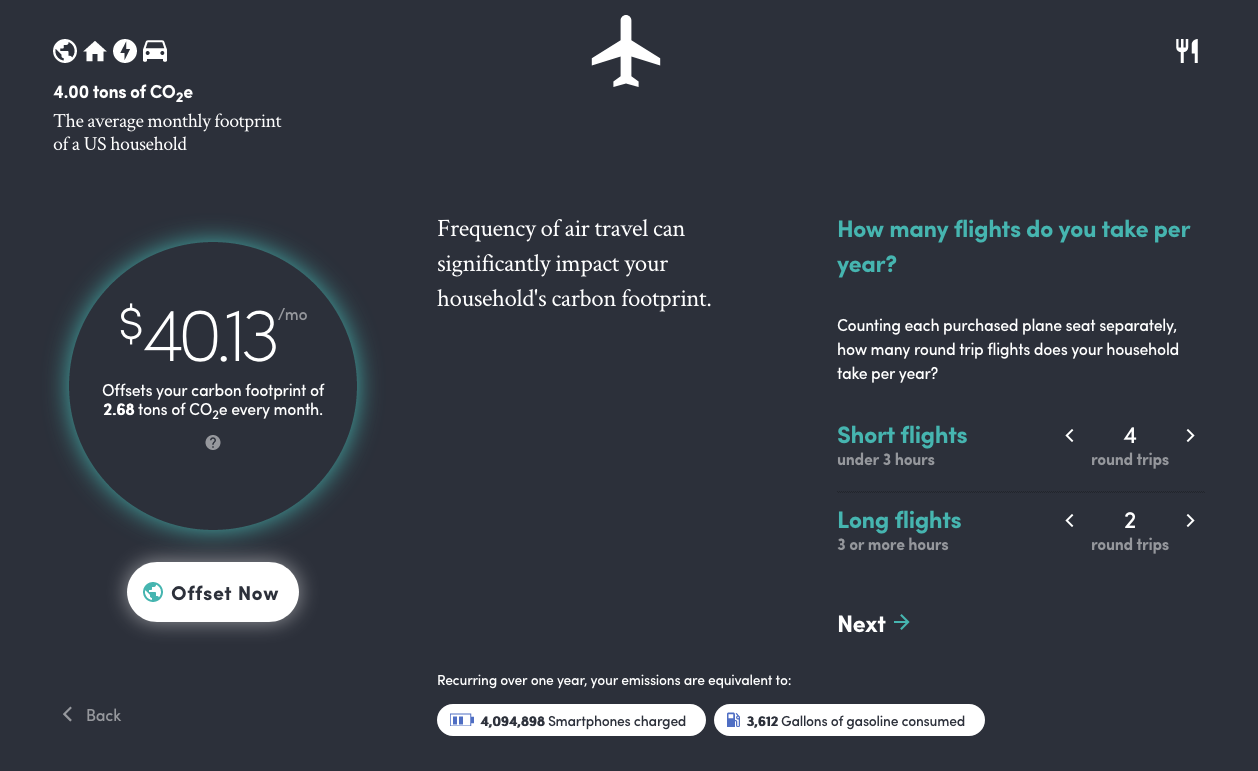

Step 1: Estimate Your Carbon Footprint

The average American’s footprint is roughly 2 tons per month, but you can always find a more detailed calculator tailored to your specific lifestyle habits. Tradewater’s calculator is a good example here. It estimates that my household (my wife & I) emit around 2.7 tons/mo.

Step 2: Purchase Offsets

I kind of already spoiled this step with the screenshot above. As you can see, you can purchase 2.7 tons of offsets from Tradewater for $40.13. Set up a recurring subscription with your credit card of choice and you’re done!

Here’s the thing. None of that is wrong but it definitely isn’t right either. Earnestly committing to net zero is incredibly complex, extremely expensive, and riddled with philosophical questions that cannot be universally answered.

Problem 1: Calculating A Carbon Footprint

While Tradewater’s calculator is a good tool to help understand how your lifestyle choices impact your carbon footprint (especially airplane flights!), it tends to leave out a lot of indirect emissions. When I eat meat it doesn’t cause emissions — the raising, processing, storing, and transportation of the meat does. That’s an indirect emission, and the only one they include. Now think about the indirect emissions for every Amazon box that gets delivered to your house. Every new thing you buy — every new car, light fixture, bottle of whiskey, and rug. Every dog, cat, and fish, and child you care for. Each has their own bundled emissions.

But what about things that will reduce emissions in the future — like solar panels, a new electric car, or better insulation for the house? What about the carbon-sequestering 2x4s that a carbon-emitting truck delivered?

What about the stocks I own? Am I responsible for that company’s emissions because I invest in them? If my company pays me to fly somewhere, am I responsible for those emissions or is the company? If I hire gardeners that use a gas leafblower on my property, are those emissions mine? Or should I only feel deep shame for ruining the lives of my neighbors?

And what about my lifetime emissions up to this point? Should I be responsible for my emissions since birth? My emissions in adulthood? Just the emissions from today forward? What about the emissions of my ancestors? If I inherited a house from my grandfather, who’s responsible for the emissions of constructing that house?

My Approach

I’ve settled on mostly ignoring calculators. By and large, an individual’s emissions scale with their income, not their choices. A billionaire vegetarian is going to be responsible for several orders of magnitude more emissions than an average earning carnivore. That being said, the EPA estimates the average American emits around 2 tons per month. Here’s my formula:

1 + [income factor] + [airplane factor] = monthly C02 in tons

This is imprecise, subjective, and by far feels the most correct. Do you believe your income puts you at about twice the level of consumption as a typical person? Maybe your income factor is 2. Do you only fly a couple times a year? Your airplane factor could be 1. Do you fly a private jet every month? Your airplane factor is probably closer to 10 or a 20.

Feel it out. I’m guessing my footprint lies between 1-10 tons/mo, and 4 tons/mo feels like a good guess. I spend a lot of money, but I also rarely fly and think about the carbon impact of my choices more often than not.

Now, how about lifetime emissions? There are some things I would definitely say I am responsible for — like the new house I’m building. That’s 100% on me. And since my goal here is to leave the world a better place carbon-wise than when I found it, I’m going to say I’m responsible for all my emissions since birth, understanding that I wasn’t wealthy until very recently.

75 tons/house × 1 house

+ (35 years × 2 tons/mo + 2 years × 4 tons/mo) × 12 mo/yr

= 1,111 tons

Final Answer: 1,011 tons + 4 tons/mo

Problem 2: Offsets Are Different Types of Negative

I’ve been using Tradewater as an example because they have a beautifully designed website, their offsets are pretty cheap, and because refrigerant management is a key strategy in winning our battle with carbon. But there is a big caveat here: Tradewater doesn’t technically remove carbon. They prevent potential carbon from being released — they avoid future emissions. This is much different than a company like Climeworks that deploys large machines that suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

Both of these are negative emissions, and any negative number cancels out a positive number. But I can’t convince myself that purchasing offsets from Tradewater for a flight I take tomorrow is a fair trade. It doesn’t actually feel like I’m offsetting my daily life. It feels a bit more like paying for past mistakes.

My Approach

For all of my future emissions, I want to purchase offsets from removal projects like Climeworks and Charm Industrial. That means 4 tons/mo + 75 tons/house. Any emissions I fail to offset from 1 year ago (when I started offsetting) forward get added to a one-time removal deficit.

For all of my past emissions, I want to purchase offsets from avoidance projects like Tradewater. That means paying down a historical debt of 864 tons.

Problem 3: Low Quality Offsets

The vast majority of offsets you can purchase today are extremely low quality. Does it involve a forest? It’s probably not actually removing any carbon. The good people at (carbon)plan have built a CDR (Carbon Dioxide Removal) Database that helps illustrate this. Quick — go filter by projects with the highest rating.

One result.

The quality of an offset is important! I don’t want to say the vast majority of the carbon removal industry is filled with hucksters and con artists… but if someone plants a tree, counts it as sequestering carbon for 100 years, then cuts down the sapling next year — did anything actually happen? No carbon got sequestered — but you sure got conned out of your money. Here are some questions to ask about a potential offset before purchasing it:

-

Does it remove carbon that otherwise wouldn’t have been released?

Capturing carbon from a natural gas plant isn’t better than just shutting down the plant. -

Is the carbon permanently sequestered?

Saving a rainforest today doesn’t stop someone from burning it down in the future. -

Does it create new emissions elsewhere?

Growing a tree for lumber sequesters carbon, but cutting it down and transporting it releases carbon.

I probably don’t need to tell you that high quality offset projects are far more costly than low quality projects.

My Approach

I want to purchase offsets from high quality projects, even if that means I am offsetting less than I am emitting.

Problem 4: This Isn’t An Industry Yet

I love Climeworks, but the process they use requires cheap geothermal energy and specific types of basalt bedrock to mineralize the carbon dioxide. In other words: it only works in a very small part of the world and can’t be scaled to anywhere near our current level of emissions. It’s also crazy expensive ($1000/ton)! Can you imagine the typical earning family adding a $2,000/mo bill for every household member? We can’t rely on Climeworks to offset the world’s emissions.

In order for net zero to be effective globally, carbon offsets need to be a mature industry with solutions that can be deployed cheaply all around the world. We aren’t there yet — any offsets you buy in 2021 are really kind of proof of concept. A bet on our future.

Part of why I subscribe to Climeworks is to offset carbon, but really I see myself as investing in their technology’s future.

My Approach

I want to purchase offsets from a portfolio of projects so that I can invest in many different carbon sequestration technologies because large-scale deployment relies on multiple methods of sequestering carbon.

Where I’m At

I’m not at net zero. I’m net zero ish. I’ve started. You can see a full breakdown over at my offset page where I’m going to try to keep a running total. Here’s the punchline as of today:

- I spend $1,500/mo

- I offset about 35% of my monthly emissions (removal)

- I have paid down 31% of my historical emissions (avoidance)

- I have a debt of 106 tons of one-time emissions (removal)

Why do I spend $1,500? Because I decided to give $500/mo to Climeworks about a year ago, then decided to continue that amount to other high quality projects I’ve found since then (Charm Industrial and Tradewater). Could I afford to spend more? Yes. If I had a typical income would I spend this much on carbon offsets? Absolutely not.

Why don’t I just pay for the offsets as I laid out above? It’s a good question. I hadn’t really given it much thought until I wrote this article. I probably should.

I dunno man! None of this stuff really benefits me. Another way of looking at this is that I set $1,500 on fire every month for no return. Then again, I’d love to live in a future where I can fly private and not feel like a shitheel.

And you know — isn’t that kind of the whole idea behind carbon offsets? If you are paying for high quality carbon removal equal to your emissions, I see no moral reason not to say you are actually living net zero. But maybe it’s also worth remembering that we don’t have great math for calculating our emissions, and offsets as they are priced today are only feasible for the ultra-wealthy.

The vast majority of the world isn’t even close to being able to pay for carbon offsets. They have no hopes of living net zero. And most of those people — especially those in the Global South — will suffer the most as the result of climate change. Maybe in that framework, net zero isn’t enough.

But don’t let that stop you from starting.

The Climate Gap 28 Sep 2021 4:00 PM (4 years ago)

If you’ve spent any time looking into climate change, you’ve heard a lot about emissions. Climate change is fueled by our emissions of greenhouse gasses and we must reduce our emissions to avoid disaster. Disaster is usually spelled out in some degrees of warming, usually 1.5˚C or 2.0˚C. In order to avoid this disaster, we are given two actionable items:

-

As individuals, we must reduce our personal emissions. We need to put solar on our homes, buy electric cars, get rid of our gas appliances, etc.

-

Collectively as the world, we must re-engineer our industry and means of production to reduce emissions by the gigaton.

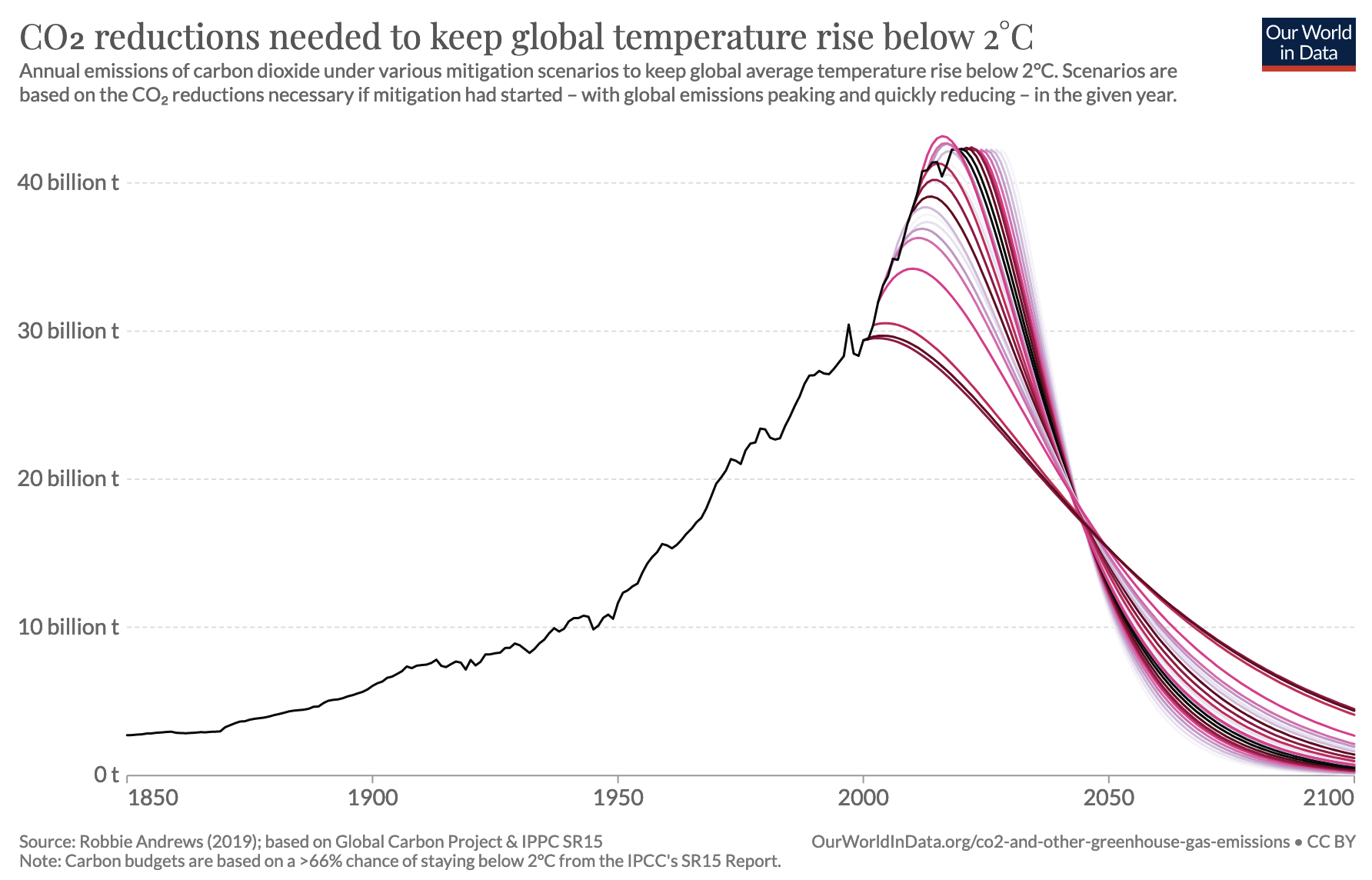

You might even be familiar with a graph that looks something like this:

It doesn’t take much critical thinking to realize something pretty quickly: none of those projected curves are actually going to happen. We haven’t even started pointing the graph downwards yet. We will not decarbonize the entire world in a few decades.

So — okay. We aren’t going to limit warming to 2˚C by reducing emissions. What are our options? The next thing you’ll hear is carbon capture and carbon sequestration. Plant more trees, install CCS (Carbon Capture and Storage) devices on natural gas plants, build DAC (Direct Air Capture) machines to suck CO2 out of the air. We’ll create a negative component to the chart that adds a possibility for positive emissions to be balanced by the negative emissions of carbon removal — reaching something we call net-zero emissions.

Unfortunately, planting more trees and other natural sequestration solutions aren’t a path out of this. At best, that sequestration happens once. If we reforest a region and it sequesters a few gigatons of CO2, that forest doesn’t keep regrowing year after year — it is a one time offset. At worst… how much carbon does a forest sequester once it’s burned down? We need a way to capture and sequester emissions on an ongoing basis. That means CCS and DAC.

Across the globe in 2020, we captured and stored 0.000009 gigatons of C02 with DAC and 0.04 gigatons of C02 with CCS. In order to capture half of our current emissions, we’d need to be capturing around 20 gigatons per year, or 500 times our current CCS capacity and 22 million times our current DAC capacity. But this is only part of the story — the vast majority of that captured carbon was used for EOR (Enhanced Oil Recovery). In other words: the only realistic implementation of carbon removal so far is to extract fossil fuels that would have otherwise been unprofitable to extract. I wouldn’t call that negative emissions.

It’s pretty clear that carbon capture and sequestration on the scale required to limit warming to 2˚C isn’t going to happen.

The Cure is Also the Problem

Reducing our current emissions to zero is only half the struggle. We also need to find a way to compensate for the emissions needed to get to that decarbonized future.

We all agree that we need to replace our gas powered cars with electric cars, replace our coal energy plants with nuclear and renewables, and so on and so forth. But building electric cars, nuclear power plants, and solar panels emits CO2 in the process. Electric cars require batteries that use materials mined with diesel tractors. Nuclear power plants are made of an incomprehensible quantity of concrete. Solar panels require aluminum that must be smelted from ore. This list goes on and on. It’s going to require an incredible amount of emissions to build the infrastructure we need to reduce emissions.

At the same time, all around the world people are escaping poverty, moving into the middle class, and generally improving their standard of life. That means more apartment complexes, more iPhones, and more foam mattresses. All of which cost emissions to make.

We cannot ethically or reasonably deny these things to the developing world. Thanks for letting us burn fossil fuels to get where we are! Now you need to lift yourself up without creating any more emissions — that good? The idea is unconscionable and counter-productive. If we want to solve the emissions problem, we’re going to need the cooperation of the entire world. Subjugating the majority of the world’s population into poverty isn’t going to cut it.

Fuck

We aren’t going to limit warming to 2.0˚C through emissions reduction, and there isn’t a credible reason to believe we have a path to reduce emissions at all over the next few decades. The gap between what is necessary and what is feasible is so large as to be effectively meaningless.

Do you know how many footsteps it would take to walk from the Earth to the Moon? Would having that answer get you any closer to the moon? That’s the kind of gap we’re talking about. We are talking about an entire restructuring of the world’s governments, industry, financial systems, agriculture, transportation networks, and every single human’s way of life. Oh — and the complete dismantling of every country’s war machine. It’s not worth investigating because there is no way it will happen in time to prevent warming in the way our charts imagine, just as you will not be walking from the Earth to the Moon no matter how many footsteps it measures out to be.

Fuck. Fuck Fuck Fuck.

Paradigm Shift

The above conclusion can be pretty depressing. Doesn’t that mean the world is ending? No. It’s not. But our current paradigm surrounding climate change is in need of serious repair. I’m often reminded of something an old rancher once told me when I was trying to figure out how to fix the dirt road to my off grid property: sure you can fix the road, or you can just buy a bigger truck.

Reducing emissions is incredibly important. We have to find a way to decarbonize our way of life if we want to life comfortably on this planet. But we aren’t going to combat climate change in a meaningful and timely way focusing on emissions. We need a solution to the emissions problem, but it isn’t going to be our answer to climate change. Not in this century.

Once I freed myself from this obsession of solving an unsolvable problem, I realized that the emissions paradigm had been an immense burden. How can it not? The only effective way to reduce your emissions to zero is to cease being. The only way to reduce our world’s emissions to zero is through world wide revolution toward…. something else we only have faint ideas about? What’s worse — this obsession with emissions blinded me from possible solutions. If we take it as fact that emissions will continue to rise over the next hundred years, what are our options? What’s our bigger truck version of combating climate change?

We have to break out of our current paradigm.

Resilience and Mitigation

I believe our most viable tools in combating climate change revolve around resilience and mitigation.

Resilience is adapting our infrastructure to live in a world of changed climate. It means building houses that suffer floods and wildfire undamaged. It means neighborhoods built so that neighbors can support each other. It means levees seven stories high and tractors that work in deep mud. It means energy systems that continue to function even as the grid fails, purification systems for contaminated water sources, and air handling systems designed for toxic air.

Mitigation is a different thing. It means reducing warming even as emissions rise. It means solar geoengineering, cloud seeding, and a variety of other incredibly uncomfortable ideas. It’s scary and full of terrible outcomes. But I believe it’s a necessary and inevitable step to buy us time while we work on the emissions problem. Inevitable because solar geoengineering isn’t that expensive and most companies / countries have the means to start a project. Rogue geoengineering will absolutely be a thing. It’d be nice if it wasn’t rogue.

These are no small tasks. We’ll need to change the way we think about housing, transportation, land ownership, food, energy, and what “the environment” means just to live in the world that exists today. But these ideas are far more approachable than avoiding climate change with emissions. I can imagine a house built to survive a wildfire. I cannot imagine every single government, industry, and human on earth voluntarily changing their way of existence in order to to reduce emissions to zero, then negative.

I’ll say it again: reducing emissions is incredibly important. We have many viable paths to do this! We just don’t have any paths that work on our given timeline. So I look at emissions as a research project — probably the most important research project of our generation. We have to decarbonize our way of life. We have to build an industry of carbon removal. We have to remember that every pound of CO2 we fail to emit is one pound less to be removed in the future. Paving a path toward solving the emissions problem will be our gift to the children of 2150.

So I’ll keep my subscriptions to Climeworks and Tradewater to buy back the carbon I emit. I’ll invest in Regenerative Agriculture and novel uses of farmland. I’ll continue giving to Carbon 180, Clean Air Task Force, Cool Earth Action, Project Drawdown, Protect Our Winters, Sierra Club, Trees for the Future, and other emissions focused organizations. I’m not giving up on the most important research project of our lifetime.

But I’m not going to pretend this will have any effect on the challenges of my generation, or even the next. It means I’m going to tell you that the important part of my new house isn’t the electrified induction cooktop — it’s the HEPA filter and backup batteries. And I might even fly on an airplane or three and find joy in life without measuring every gram of carbon I emit.

Our way forward is through a changed climate. We can’t keep pretending there is some mythical singularity at 2˚C we can prevent with emissions control. We already live in a changed climate. It’s time we acted as though reality is real.

The Old Log Cabin 31 Aug 2021 4:00 PM (4 years ago)

For those of you who don’t know, I own an old high elevation cow camp in the Sierra Nevadas with my friend David. It’s home to a 99 year old hand-hewn log cabin, a chainsaw milled post & beam horse barn, and a few smaller bunk houses. It’s been a source of great joy and fulfillment over the years. We call it Leaping Daisy, or sometimes just The Ranch.

Now for the sad part: the rancher who grazes cattle around the ranch called yesterday, and let me know the old cabin and all the bunk houses burned down in the Caldor Fire.

Jessica and I have put a lot of work into the cabin the past couple of years — it was a particularly good escape from the beginning months of the coronavirus lockdown. We cleaned it up, fixed the plumbing, replaced the chinking, put a fresh coat of stain on the old logs, and very nearly removed the resident mice.

We may have owned the cabin, but it wasn’t really ours. It was a relic from the Old West, a place where the cowboys would come after a long day of rounding up cattle, start a fire in the wood stove, and fry up some chicken for dinner. It was a building that invited stories and encouraged the imagination. What did this place look like in 1922 when they cleared the land and built the cabin? What kinds of tools did they use? How did Bungie lift those roof rafters by himself when he replaced the roof at the age of 65?

It’s sad, but it isn’t tragic — this is what living in the mountains means. To choose to live in the mountains means you choose to live in the midst of powers far beyond your control. It means preparing for the weather, respecting the terrain, wrapping your arms around trees five feet in diameter, and climbing boulders bigger than houses. And it also means living with wildfire. There is no fire-free option for our forests. We burn them, or we watch them burn. This time we watched them burn.

I’m grateful for all the memories we made at the old cabin, and I’m glad so many of you were able to experience it while it was still around. Its story is finished. A hundred years ago someone cleared the forest to build a cabin, and yesterday the forest took it back.

This is hardly the end for Leaping Daisy. For now, the old barn still stands, the UTV sits safely in its shed, and the solar shed is still up and running and providing WiFi for the embers. The underbrush has burned away and many healthy trees remain standing. The forest is resilient.

The joy of the ranch has never been in the having — it’s been in the doing. There’s a little less to have now, but there’s still plenty to do. We’ll have to buy some new chainsaws and dig a new outhouse. Then maybe we can get started on something to inspire stories for the years to come.

There is something else.

Fire is a big subject in California. We don’t have hurricanes, we don’t have tornadoes, but we do have fire. And fire season is getting worse. Extreme fire behavior is the new normal, and megafires like the Caldor are becoming more frequent.

And you know? A lot of people believe there is some kind of fire-free solution. Some people believe we live in a state where logging is illegal, even though our forests are logged constantly. Some believe there is some kind of forest management fairy that will fix all of this, despite the practice’s track record of failure. Some believe we need more prescribed burns, but that it needs to be 100% safe to happen. Some believe that CALFIRE purposefully sets wildfires to maintain job security. Some people should spend less time watching infowars and more time in meadows.

No one who says these things really lives in the mountains, despite where their address might lay on a map. They are stuck in a mindset of control — of getting what they want and forcing their will upon the world. This is a disastrous way of thinking, and it is incompatible with our future. It isn’t how the old timers approached the past, and it can’t be how we approach the future.

I spend a lot of time living in the mountains. Talking to the ranchers who have grazed the National Forest for hundreds of years. Meeting up with the rangers who clear the roads every spring. Kicking the drunk hunters off my roads. Wandering the meadow with foresters. I’ve snowshoed through five feet of fresh snow, dipped in ice cold streams, and used a chainsaw taller than me to take down a 200ft tall fir. The reality of the mountains is very different than talking points on TV and the memes posted by “retired loggers” on Facebook.

The forest around the ranch was logged heavily over the past three years. After the logging crews came the masticators and wood chippers. This was all in preparation for a series of prescribed burns, the first of which escaped its boundaries and became known as the Caples Fire. This fire received massive backlash from the community despite no structures being lost and the fire’s objectives being met in majority (burninng of underbrush, retention of large trees).

Even with the massive amount of logging, mastication, firefighters, dozers, airplanes, and helicopters, the Caldor Fire ripped through this forest without care. It leapt across hundreds of clear cut properties owned by Sierra Pacific Industries, jumped over firebreaks six blades wide, and created spot fires up to a mile away. The only place it did stop? At the burn scar for the Caples Fire, the one that so many believed to be reckless.

Decades of preventing fire, extended drought, and a changed climate have all converged to create conditions for extreme fire behavior. There is no easy fix, and there are no safe solutions. We are going to see a lot more fires in the West.

There is no fire-free option for our forests. We burn them, or we watch them burn.

Toward a More Resilient Future 22 Apr 2020 4:00 PM (5 years ago)

It’s been about seventeen years now that this website has been my little corner of the internet. It’s gone through a few different iterations in those years — some sarcastic, some serious, and some arbitrarily personal. Many of those iterations are lost to poorly exported databases, absolute positioning, and the whims of archive.org. So it goes.

I’ve wanted a new Warpspire for a while now, but I’ve struggled to figure out what it should be. My initial instinct was to start with the content — because we all know that’s the best way to build anything important. Content is King and all that jazz. Wait — do people even say that anymore? I guess I still believe it. So I wrote. I made outlines, collected notes, revised drafts. I thought about where I wanted to go in life — no — where I should go in life. I wrote more. I kept iterating. None of it ever felt right.

But you know, Warpspire isn’t important. I forgot that. I don’t think there’s anything of purposeful value here. I’ve made some good arguments and some bad arguments, but there’s nothing on this site that is revolutionary or essential. When Warpspire has been at its best, it’s been a place just for me — not a thing for anyone else. I’m not really an expert. Not a genius. I’m just figuring out the world through my own eyes.

My world has changed pretty drastically over the past few years. Or is it a decade? I don’t even know anymore. I’m not sure it matters. Here’s the thing: the entire world has changed in the past ten weeks. Whatever comes next is going to be different.

It feels like time for a new Warpspire. Not one of the versions I’d outlined — those potential futures have been left behind. This is something new, something with space to grow. It’s exactly what it needs to be: a website that doesn’t know what it is yet.

Yes, all of the old links work. I am not a monster. The world changes, but it always remembers.

It feels very much like the world right now. We had a lot of ideas that weren’t working very well. So much of our world was just teetering on the edge of failure when the cliff fell out from under us. We find ourselves Wile E. Coyote floating in the air above a ground that isn’t there anymore. We haven’t started to fall yet, but it’s not like the cliff is going to come back any time soon.

I know a lot of people think things will go back to normal when this is over (and that there is an “over” to be had!). They believe this is just a hiccup, everything is still on track just maybe a little delayed. I’m not so sure. Revolutions need not be interesting. They are often quite boring.

We just hit pause on most of the modern world and we don’t know what that means. One thing I do know is we’ve been presented with an opportunity. Opportunity for growth. Opportunity for corruption. Opportunity for failure. Opportunity for something new.

I want that something new to be more resilient. I don’t know exactly what that means, either. I only have fragments. I guess that’s kind of what I want this place to be for now. Fragments toward a more resilient future.

Fragments

Can we take whatever this hamster-wheel idea that is The Economy, mash it up in a blender, and come out the other side with a hamster-wheel that pushes toward a healthier planet and a better society?

- Healthcare

- Education

- Food

- Water

- Shelter

Everyone should have this. We should give them these things because they are good things to do. It does not matter whether people deserve it, who qualifies as a person, or how we will pay for it — these are distractions. It matters that we believe it is right. If it is right and it is possible, we should do it. It is definitely possible. And I am certain it is right.

Kim Stanley Robinson on Making the Fed’s Money Printer Go Brrrr for the Planet.

We have plenty of work for people to do. Work that is far more fulfilling than running in the hamster wheel of the economy. The New New Deal? The Green New Deal? These are too small. I wish we had a progressive wing in America. We have a lot of interesting work that would be good for the planet and its people. And we just don’t do it? I’ve never understood that. What if we did good things because they are good?

This is frustrating. I do not have the answers. I really wish I did.

The Future of Work is a very real thing right now. Not in that silly way Venture Capitalists talk about it: when an employer forces you to use a website, that doesn’t mean it’s the future of work. That’s just a website. Sorry.

The current state of work is rapidly morphing into a new hierarchy of classes. The Owners. The Work-From-Home. The Warehouse Shufflers. The Line Cooks. The Delivery Drivers. This is a scary look. It does not fill my heart with good feelings.

There are promising looks! Many who work from home now always could have. We never needed to commute. And we sure didn’t need that massive office building. It turns out that yes, most meetings could have been emails. Most emails need never have been sent. We never needed to fill our air with pollutants. We can do all kinds of work just fine without burning millions of gallons of jet fuel.

John Roderick and Merlin Mann in Garbage Island. An introvert revolt! Load up the office with mylar balloons — I’m staying at home. I love it.

The Extroverts are not the problem. And the problem with the Introverts is that we think the Extroverts are the problem. And the problem with Extroverts is that they don’t think about Introverts at all.

The scales are definitely tipping in favor of the Introverts right now. I wonder if they will take advantage.

The Future of Living is another thing I think about a lot. You can live your life without ever coming into contact with the act of living these days. Washing your sheets. Gardening. Cooking. Building a deck. Sweeping the floor.

There is inherent value in spending more time in the act of living. It is likely to be the antidote for the anxiety of the modern world. We are all spending a lot more time living these days. It is not an antidote for anxiety. This is a troubled thesis and needs a lot of investigation.

43 minutes of Shawn James in the act of living.

Regenerative Food Production. Tahoe Businesses. Carbon Removal. I’d love to invest in you! I’m a terrible correspondent. I’m sorry.

I’m probably not interested in your app.

Books of the moment:

- Masanobu Fukuoka — One Straw Revolution

- Kim Stanley Robinson - 2312

- Charles C. Mann - 1491

- Susan Cain - Quiet

- Isaac Asimov - Foundation, Second Foundation, Foundation and Empire

Apparently, I like books titled after dates.

Your community is what you make it 19 Oct 2017 4:00 PM (8 years ago)

I know of a man who owns land in Montana. His dream is to prove a theory about design. For a small sum of money, you can lease some of this land — about a week’s worth of San Francisco rent will get you an acre for a year. Build a house. Plant a garden. Raise some pigs. And you can use his tractors, too.

But you can only do these things under his rules. His rules are somewhat strange to most people. You cannot use paint. You must listen to 200+ rambling podcasts. You cannot import compost from outside the property. You cannot use plywood. You can’t smoke pot. His dream, his rules. It has been slow recruiting people to join his effort. But that’s okay. It’s his rules, and he wants a community after his own design. He has chosen exactly what he wants his community to look like: people like him.

Can you imagine having an acre of land for cheaper than a week’s rent in San Francisco?

There has been much hand-wringing in the software community as of late as to what role product companies have in shaping their communities. Reddit struggled with hate groups organizing themselves in their forums. Because if we kick one group out, where does it end? Facebook has become the place that foreign powers manipulate US elections through advertising. Because what is the difference between opinion and facts, anyway? And Twitter, of course, has become a favorite home of white supremacists and nazis. Because you’ve got to be objective. In each of these cases, the companies have vehemently defended the rights of these obviously-bad people to use their service, while the vast majority of their users tell them to kick these obviously-bad people out. “It’s complicated,” they claim. A silly excuse for a company with thousands of highly creative intelligent people.

Despite what the executives of these companies may say, this shit is not complicated. Your community is what you make it. If you choose to make no rules, you have still made a rule. If you choose to give nazis a voice, you have chosen to make your community nazi-friendly. Rebranding that decision under the guise of free speech or objectivity makes no sense. When you make an environment friendly for nazis, it is a nazi-friendly environment regardless of the reasons it happens to be friendly for them.

There is this dream often used as justification. A digital platform that connects all with absolute freedom of speech. A modern day utopia of radical ideas being exchanged in a completely free environment. Executives say they have a moral responsibility to make this idealistic dream a reality. It’s a very Ayn Rand idea. It is important to remember that Ayn Rand wrote fiction.

In the real world, we often sacrifice our ideals because of the messy nature of reality. Capitalism… except for those subsidies. Freedom of religion… except no suicide cults. Second amendment rights… except no automatic weapons. For every ideal, there is always a reality. A reality where you have to draw the line — a subjective line — in order to preserve our morality, integrity, and way of life.

Your community is exactly what you make it. The man in Montana has lost members of his community because of his rules. Twitter has lost members of its community because of their rules, too. In fact it’s much worse — good natured people aren’t so much leaving as they’re getting poisoned and becoming toxic. The only thing worse than losing a user is turning them into a toxic user.

Twitter believes that somehow allowing everything means they’ve created an environment that’s friendly for everyone. But often times it’s important for a community not to have a person in it. Imagine a party with ten of your best friends. Now imagine a party with ten of your best friends and one nazi.

That is the really important thing about communities: they are made both of what you include and what you exclude, and each of those have equal weight. Not having a particular person is just as meaningful as having a particular person. It is the same with music: without rests, music is just noise.

I’ve long thought that product designers make their jobs seem far more complicated than they really are. Industry leaders act as if every decision is irreversible and of ultimate importance. But it’s not that complicated. It’s not some kind of tenth dimensional ethical chess, it’s just a lot of messy work that requires constant recalibration. You can have an open community and still kick out nazis. You just kick out the nazis. How can you call it an open community if you don’t allow nazis? Because you don’t want fucking nazis in your house. That’s it.

And maybe that decision will come back to bite them. But for science’s sake — can that potential consequence really be worse than having nazis in your house?

Next 23 Mar 2017 4:00 PM (8 years ago)

So, what is it you do all day?

I sort of disappeared a few years ago. I had a simple but difficult decision: stay and help GitHub to help grow the company or leave and help my family when they needed help most. In the space of a couple of weeks I quit my job, packed up my belongings, and moved out of San Francisco.

Ever since then, I’ve struggled to describe how it is I spend my time to my peers. Discussing the practicalities of caring for someone with a neurological disorder is not exactly small-talk worthy, nor is it something I particularly want to discuss with strangers. There’s also the unfortunate culture in technology that devalues everything unrelated to militant capitalism. If you’re not trying to make money, what are you even doing? Now add on to that the few that saw my vulnerability as an opportunity for leverage — and indeed — leveraged the fuck out of me. It’s all added up to be an interesting couple of years.

So when people ask what it is I’m doing, I’ve mostly kept it light. I tell people I’m semi-retired. It’s not entirely untruthful — I’ve spent a lot more time outside and doing fun things — but it’s a lot less than the whole.

That being said, I’ve been working hard for the past few months to find more space for me again. Which also means I’ve been thinking more about what’s next.

A lot of people talk about passion with regards to work — that feeling of endless energy one feels when their inner desires meet application. Work no longer feels like work, and all questions of is this worth it? and am I doing the right thing? feel silly and irrelevant. I used to have a lot of passion for software. Whatever I have now is different.

I feel torn between the endless opportunities I see in software and the disgust for what our industry has become. The rational part of my brain tells me you don’t have to be like those terrible people to work in software, but the emotional side of me sees what our industry is doing in practice and doesn’t want to be associated with it at all. You can still do good work and be employed by Exxon, but at the end of the day you’re still working for the oil industry. Is that who I want to be?

I’ve spent a lot of time asking myself why I am so frustrated with our industry, and I think I’ve narrowed it down to two common themes:

-

The routine manipulation of employees, gig or otherwise, through complicated legal structures (1099’d full-time employees, stock option agreements, expensive lawyers, employment/termination agreements, etc).

-

The routine manipulation of customers through complicated technical structures (selling data without permission, outright spying, bricking expensive hardware to avoid liability, etc).

To work or participate in the technology industry is an exercise in minimizing manipulation (or, if you’d like to be rich, maximizing it). This feels shitty in a tremendously heavy way.

What happened to the idea of building great stuff that people are happy to pay for? What happened to the idea of treating employees as people and not legal entities to extort? Were these fantasies of a naive 20-something Kyle, or a reasonable idea of how our industry should act? Why do the needs of the corporation always seem to outweigh the needs of people? Honestly, it’s all driven me a bit crazy. But more relevant to this essay: this shitty-ness has eroded my enthusiasm for building software.

That’s a bummer.

Something I have been very enthused about as of late is permaculture, or at least many of the ideas that circle around that particular label.

What I love most about permaculture is that it transforms the laborious step-by-step annual process of contemporary gardening into systems design. Instead of remembering to water each of your plants every day, you set up systems to capture water so you don’t have to irrigate. Instead of measuring out fertilization schedules, you design plant systems that provide the nutrients each of them needs. The end result is that it makes gardening a lot more like programming. It takes more effort up front but the result is a self-sustaining system rather than one that requires re-building each year. That means this year’s effort adds onto last year’s — constant effort results in ever-increasing production. Permaculture takes this idea and applies it to all of the ways we live. How can we apply systems design and the forces of nature to design a more self-sustaining house? How can we use these principles to design our neighborhoods?

The shape of America we know today — endless rows of almond trees and corn, factory farms, tract houses, and suburbs — has always felt a bit off. We face incredible challenges in the years ahead, and these existing structures are not serving us well. Our cities are not designed for people, our homes not designed for their climate, and our farms not designed for farmers. Like a hammer who wants everything to be a nail, we are a barrel of oil designing the world with petroleum-tinted glasses. And what happens when we expand to planets that doesn’t have such abundant petroleum? Wouldn’t it be productive to practice harnessing the implicit energies of a planet?

The engineer in me can’t stop thinking there’s got to be a better way.

Many environmentalists believe the answer lies in conservation and consumer choices — reduced energy use, less intensive farming, and voting with your dollar — but I’ve never believed those strategies to be sane. You cannot deny the third world and the poor the modern conveniences the rest of us have. We achieved those conveniences with petroleum, but that’s no longer a sane path. We must find a new method for the rest of us. I also believe that a world with abundant (and excess) energy is a world in which humankind thrives and advances. To practice energy conservation on a civilization-scale is to stick our heads in the sand and refuse to grow.

I believe we can live in comfort and abundance while also living in greater harmony with nature (aka not fucking up the planet for our children). This isn’t blind environmentalist ideals — it’s working in a way that leverages nature’s built-in energies instead of fighting against them. Fresh water is scarce, yet we fill our toilets with fresh water just to defecate into it. Homeless starve on the streets, yet we plant non-bearing fruit trees along our city streets. Our homes require constant air conditioning, yet we bulldoze the trees on the southern side of our homes. All in all we’re just making a lot of bad decisions right now. I see permaculture as a framework to make better decisions through design, but for the environment.

This is a big part of what’s next for me. Last year, I became part-owner in an old high-country cattle camp / working forest near Tahoe. This is where I want to explore more of these ideas and share them with others. We’re building a place to get away from the craziness of the modern world and explore examples of living in comfort & abundance in harmony with nature. Call it part working forest (growing trees for profit), part getaway, and part laboratory.

David and Alia enjoying springtime in Leaping Daisy's meadow.

David and Alia enjoying springtime in Leaping Daisy's meadow.

It’s called Leaping Daisy. It’ll be a while.

Despite the first half of this essay, I’d be a liar if I said I wasn’t still interested in software. I’d like to think I’m just going through a rough patch in our relationship right now. Plus, Leaping Daisy sits under about seven feet of snow as we speak, so the winter leaves me with a lot of time alone with my thoughts.

For a long time, I was mostly interested in software that made money. Finding the sweet spot between customers, willingness to pay, and profitability is fun. But Venture Capital and their fleet of lawyers have become experts at warping and extorting these kinds of products. They’ve taken the fun out of making money. As such, lately my interests have been more ideological than profitable.

I’ve started and abandoned dozens of projects over the past couple of years — some silly, some ambitious, and some just plain dumb. So I’ll be honest: I’m not really sure what’s next here. I’ll say there are a few areas of interest that seem to keep popping up in my head:

-

Data Ownership, Privacy, and Cloud-less Software

It feels as though we’ve embraced the cloud a little too much the past decade or so. While there’s tremendous benefits to centralized online services, there are also a great deal of downsides. Customers rarely own their data, companies routinely cooperate with state-run surveillance programs, and privacy & security continues to be a nightmare.There’s a lot of room to explore software that doesn’t take these tradeoffs as laws of nature, but rather design considerations as they should be. I don’t think it’s time to abandon the cloud, but I do think it’s time to explore ways we can engineer around its weaknesses.

-

Civic Engagement

Thus far, most of the technological effort applied toward civic engagement has been centered around transparency, data, visualization, and hack-day type projects (unsupported software). While it would be reckless for me to say these types of efforts are a waste of time, they do not conform to my view of how government works in action. Psychology, emotion, and interpersonal relationships play a far greater role in shaping policy than any objective fact. Unlike many, I don’t see this as a problem or a bug. It’s just how large groups of people make decisions. We are not robots. We’re leaky bags of meat that have no inclination toward rationality.I want to know what happens when we take this view of humanity, leverage our skills in the soft sciences, and apply it toward civic engagement through technology. How do we take the lessons we’ve learned from social networking’s success to strengthen community bonds? How do we build better relationships between representatives and their constituents? Doesn’t it feel a little silly that we still have to call our representative (and talk to an intern) to voice our opinions? As it stands now, Facebook knows more about a district’s opinions and beliefs than its congressional representative does.

-

Tools for People

More than ever, it feels as if the term “software” is an extremely poor description of the field as it exists in the real world. It seems more and more that we have three separate industries: tools for developers, tools for large corporations, and junk food for everyone else. Tools for developers are pretty good and steadily improving. Tools for corporations (think inventory software, check-in systems, etc) are made of anger and frustration. And then there’s the FarmVilles, Facebooks, Snapchats, and Snapchat Clones that dominate person-hours spent using software. I still find that most non-developers just use Excel (Google Spreadsheets) or exist in a constant state of frustration with their software tools.We’ve been very successful creating junk food for normal people, but we haven’t been very successful in creating software that helps normal people get stuff done. Software-as-a-tool has always been the way I envision software working best. Not software that maximizes use, but software that maximizes utility.

If you’ve got some interesting projects you think I should check out, let me know (kyle@warpspire.com is probably best). Note: if you’re funded for purposes other than defrauding VC firms, think phone calls are fantastic, or think that the words stock or options are enticing, I am probably not your target audience right now.

Oh, and hi everyone! It’s been a while. I’ve missed publishing, and I hope I can find time for more of it again.

Ad Supported 16 Sep 2015 4:00 PM (10 years ago)