Gnomecast 223 – Getting Spooky with Bridgett Jeffries 3:00 AM (15 hours ago)

Join Ang as she chats with guest Bridgett Jeffries about all things spooky and scary games. Need some insight into how to bring the best of horror to your table during this spooky season? Listen to Bridgett!

Links:

Making Second Chances Cinematic: Introducing the Invocation Reroll 17 Oct 3:00 AM (5 days ago)

When it came to Auto Polo, I think the failed roll came long before this was taken.

“I’ve got a bad feeling about this…”

Famously uttered by space smuggler Han Solo as he approached a planet killing weapon in Star Wars, this line has appeared in nearly every Star Wars project since that first film. It’s very likely you’ve heard the line before; probably dozens of times. Just a handful of words, but they carry decades of cinematic weight. Everyone knows how to deliver it. Everyone knows what it means. Drop it into a roleplaying session and you’ll get chuckles, groans, or knowing nods.

It’s shorthand for one thing: something’s about to go wrong.

That’s the power of a well-timed line. It makes the audience lean in. It transforms a moment from procedural into cinematic. And tabletop roleplaying games are full of moments that should carry that weight — but often don’t.

Among the most overlooked: the humble reroll.

Admitting The Problem with Flat Rerolls

Rerolls exist in almost every system. D&D has Inspiration. Savage Worlds uses Bennies. Fate has Fate Points. Call of Cthulhu lets you “push” a roll. Dozens of narrative systems let players spend currency or invoke aspects for another try.

The shape is always the same: roll the dice, spend a resource, roll again.

Mechanically, this works great. Rerolls soften bad luck, protect characters from catastrophe, and give players agency. But narratively? It usually sounds like this:

“I’m gonna spend a point and reroll.”

“Cool, roll again.”

The dice clatter, the result changes or doesn’t, and the story lurches forward. The moment rarely lingers.

That’s ironic, because the reroll might be the most important roll of the night — the one that keeps the story alive.

The problem isn’t the mechanic. It’s the framing. Rerolls are inherently dramatic — a refusal to accept failure, a desperate second chance — but most games treat them as paperwork.

Fixing the Problem with Invocation Rerolls

The solution is simple: give rerolls a ritual.

Before a player rerolls, they speak a line.

That’s it. No new math. No rules rewrite. Just a phrase that reframes the reroll as performance.

The line could be lifted from pop culture — a weary “Oh, crap” like Hellboy, a defiant “Not today” like Arya Stark, or the classic “I can do this all day.” Or it could be original, something players tie to their characters in Session Zero: a paladin growling “I shall not fall,” or a spy whispering “Trust me.”

Of course, there’s always the genre-agnostic fallback:

“Failure is not an option.”

Other Ways to Invoke

The “bad feeling” line is just one approach. Invocation doesn’t have to hinge on a single phrase. Players can bring it into the fiction in different ways without slowing the game down:

- Signature Quote: A personal catchphrase that shows up whenever the stakes spike (“Not this again” or “Time to roll the hard way”).

- Environmental Cue: Pointing to a detail in the scene — flickering lights, a distant rumble — and tying it to the reroll.

- Character Habit: A nervous tick or ritual like cracking knuckles, flipping a coin, or checking a weapon.

- Table Callback: A communal phrase or in-joke everyone recognizes, reinforcing group identity.

- Meta-Acknowledgment: Saying the trope out loud (“This is the part where everything goes wrong, right?”).

Whatever option the group picks, consistency matters. The content of the phrase is less important than delivery. Short, repeatable, tied to the tone of the game, and spoken like it matters.

That little ritual transforms a reroll from a mechanical do-over into a dramatic beat.

A Brief History of Rerolls

Why do rerolls show up everywhere? Because they’re one of the oldest tools for narrative agency. Even early miniatures rules let players spend morale points for a second chance.

House rules for rerolls appeared in D&D almost immediately. Deadlands made them tactile with poker chips. Fate built them into its core with Aspects. All of them recognized the same instinct: players want to say, “Not like that.”

Invocation Rerolls follow in that tradition. They don’t replace mechanics; they highlight the drama that was always there.

What this Looks Like at the Table

So what does this look like at the table?

Val’s gonzo space opera tracks rerolls with plastic battery tokens. When Rook blows a roll in a firefight, his player tosses a blue battery on the table: “I’ve got a plan.” The reroll fails again. He smirks: “I’ve got 8% of a plan.” The table roars. By the next week, the line has become a running gag.

Morgan’s noir detective game uses plastic dimes. When the detective flubs an interrogation, the player flicks a dime across the table: “Luck’s just another kind of debt.” The coin spins, the dice tumble, and the moment feels ripped from a paperback novel.

Tamara’s pirate campaign uses plastic pieces of eight. In the middle of a naval battle, the captain slams one down: “Hoist the colours high!” In defiance of fate. The crew responds, “Never shall we die!”, the dice fly, and suddenly the reroll feels like mutiny made flesh.

And beyond those? In superhero games, players slam chips down with “I could do this all day.” In post-apocalyptic ones, survivors whisper “If I’m gonna die, I’m gonna die historic!” In romantic fantasy, an elven ranger invokes “I would rather spend one lifetime with you than face all the ages of this world alone.” (It’s a long one… Maybe just “One life time…” but it’s a great quote, nonetheless.

The props and phrases change, but the pattern is the same: the ritual makes the reroll memorable.

Tips and Pitfalls

- Get buy-in early. Session Zero is a perfect place to set tone. Shared phrases unify the group; individual ones give characters personality.

- Keep it short. A good Invocation is 3–6 words, a short sentence. Anything longer bogs down the beat. (But there are exceptions to this.)

- Props help. Poker chips, beads, coins, or scraps of paper make the ritual tactile.

- Adapt online. In VTTs, players can type their lines, use macros, or play sound clips.

- Mind the tone. Humor works if everyone’s on board, but check in to avoid breaking immersion.

- Don’t force it. Some players will warm up slowly. Let them see it in action first.

The Payoff

Invocation Rerolls elevate rerolls in three ways:

- Success feels sweeter. When a line lands and the dice succeed, the table cheers like destiny just stepped in.

- Failure feels richer. When the dice flop after an Invocation, it’s not wasted — it becomes a beat of gallows humor, tragedy, or irony.

- Table culture grows. Invocations become inside jokes, mantras, or rallying cries. They stop being mechanics and become part of the campaign’s shared language.

And the best part? They’re free. No rebalancing, no new subsystems. Just a ritual layered on top of what you already play.

We started with a line you already knew:

“I’ve got a bad feeling about this.”

Alone, it’s just words. At the table, it sets tone, builds anticipation, and makes everyone lean in.

That’s exactly what Invocation Rerolls do. They take the most mechanical of beats — the reroll — and turn it into a story moment worth remembering. The phrase, the token, the dice: together they say more than “try again.” They say: this matters.

And once your group adopts them, those Invocations stop being rules. They become culture. The lines you’ll quote weeks later. The rituals you’ll carry into new campaigns. The heartbeat of the game.

So the next time your players stare down failure, don’t just give them a reroll. Give them a chance to make it memorable.

Let them drop the token. Let them say the line.

Because sometimes the most important part of a reroll isn’t the dice.

It’s what your players say before they roll.

A Look at The Art of Kobold Press 13 Oct 2:00 AM (9 days ago)

Kobold Press sent me a review copy of The Art of Kobold Press, a book showcasing the artwork used by the company over the course of its lifespan. That gives me the perfect opportunity to recall my connection to RPG art over the years. I was really fortunate to play RPGs in an era when some amazing artists were first defining the look of fantasy roleplaying.

When I started reading comics, I developed the ability to pick up on specific artists that I enjoyed, and could recognize their work before I even looked at the credits in the comics. This translated into my growing hobby of RPGs. The more I looked at the covers of various Dungeons & Dragons products, or the covers of Dragon Magazine, the more I saw details that would define an artist in my mind. I am definitely of the generation for whom Larry Elmore defined the Dragonlance saga with his art, and Keith Parkinson’s Gods of Lankhmar painting is burned into my brain.

The Mind’s Eye

The RPG hobby is predicated on imagination. Many of us love to envision things in our mind’s eye, creating a visual reality only we can see, based on images evoked by words. But the RPG hobby has also been an extremely visual one. That doesn’t rob us of our ability to synthesize our own unique view of the fantasy worlds that we explore, but it gives us a broader palette from which to pull imagery that populates our waking dreams.

I’ve been drawn to RPG art books from the time I first realized they existed. One of the earliest I remember was The Art of Dragonlance, which collected many of the iconic pieces of Dragonlance art that had appeared in the adventures, novels, and sourcebooks up to that time. The Art of Dragon Magazine collected ten years of cover art, which represented a staggering variety of fantasy art. I’ve picked up art books like this for years, including a new version of The Art of Dragon Magazine, this one looking at 30 years of art instead of 10, from the Paizo era of the publication. My copy of Dungeons & Dragons: Art & Arcana is sitting across from me next to cover compilations of DC and Marvel comics, and Star Wars: Propaganda.

The Visual March of Time

Viewing the art a company produces over the years tells a story, and anchors the progression of time. But most of these art books are, well, books, and they literally tell a story as well as presenting the visual evolution of a game or a company. The Art of Kobold Press is no different in that regard. In addition to pages and pages of art from the company’s publications, there is interspersed commentary about the company and the context of the art being produced.

While it is an interesting look at the company’s art over time, it’s not an exhaustive treatment of the company’s history. You can glean a lot from it, but the purpose isn’t to discuss the pioneering of crowdfunded RPG projects before the rise of Kickstarter, starting with Open Design, for example. For the art that is reproduced, the earliest Open Design projects account for much of the page count, moving fairly quickly into the Pathfinder era products and the covers of Kobold Quarterly, which already shows that Kobold Press was in step with industry artwork and keeping up with the high end of fantasy art standards.

The bulk of the volume is dedicated to the 2014 SRD era products, especially the art from the Tome of Beasts line of books, the Midgard campaign setting, and the various adventures published at the time. The last third of the book is dedicated to the Tales of the Valiant era of the company, which includes some discussion about standardizing visual elements and decisions about what needs to be front and center to showcase a new product line. It was a happy surprise to see the Riverbank RPG get six pages to showcase the divergent art style of that game, including a beautiful two page spread. Stan!’s artwork for the Necromancer card game also gets a few pages to shine. I was very happy to see the cosmological map from the Labyrinth Worldbook get a page dedicated to it as well.

Looking Forward

The art in the book includes a preview of the art that will appear in the upcoming Player’s Guide 2, including the class artwork for the new(ish) Theurge, Witch, and Vanguard classes. Seeing that art reminded me of something I wish was present in the book, a more explicit discussion of iconic characters in RPG art. It’s something Dungeons & Dragons has largely left behind (if you don’t count characters from other D&D media getting showcased for marketing purposes) since the 3rd edition era, but Kobold Press partially revived the trend in its art orders for Ghosts of Saltmarsh, has used iconic parties in their art for the Scarlet Citadel and Empire of the Ghouls adventures, and has a new set of iconic characters with the class artwork in Tales of the Valiant.

That’s not to say there isn’t any discussion of the decisions behind how the art is produced. Marc Radle, the art director of Kobold Press, provides much of the narrative, with additional insights from others at the company like Wolfgang Baur and Celeste Conowitch, as well as some commentary from game designers and artists related to the projects shown. At worst, it means that there is room for a History of Kobold Press someday in the future, that can dig into that kind of material more thoroughly.

What I appreciate most about a book like this is that it allows me to get back into the habit of putting names to artwork. One thing that is evident in a book like this is that the modern landscape of RPG artwork is much different than my early days in the hobby. When I was first entering the hobby, it was obvious when someone new like Fred Fields, Gerald Brom, or Tony DiTerlizzi began producing art for TSR. There are so many artists represented in this book that I don’t want to do a disservice to any of them by calling out just a few, but that I know who created some of my modern favorites now is something for which I am grateful.

How to Steal a Story (to Use in Your Campaign) 10 Oct 6:05 AM (12 days ago)

“Everything’s a reboot. There’s nothing original anymore.” Boring statements. Defeatist. Ironically, not even original complaints.

“Everything’s a remix.” Punk as hell. Creates opportunities. Empowering.

Whether we’re talking about Marvel movies, the latest Disney live-action reboot, or an American remake of a popular foreign film, the idea that we’ve “run out of ideas” runs rampant amongst those of us who hang out in creative spaces or care deeply about the stories we consume.

And while I don’t think this article will save us from the ump-teenth reboot of Batman’s origin story, I do think there’s something important we can take away from this storyteller’s lament — if nothing’s original any more (and really, it hasn’t been original since before Classical times) then everything’s a remix, and all stories are fodder for our stories.

So, in the punk spirit of DIY, I’m gonna tell you how to steal a story and get away with it.

HOW IT’S DONE

To steal a story, you have to step back and train your brain to look at stories like recipes. You know how a good cook can taste a dish and tell you the ingredients that went into it? (And how great cooks can then give suggestions for substitutions that would transform the food into a completely new experience?) That’s what we need, and that’s what we’re gonna learn how to do.

So, if you’re new to this deconstruction thing, start by taking notes on five key elements of the story: the characters, the situation they find themselves in, their goals, the obstacles that prevent them from completing those goals, and your favorite thing about the story.

(For the rest of this article, my go-to example will be my current obsession: K-Pop Demon Hunters, or as I like to call it, “Hannah Montana meets Buffy the Vampire Slayer.”)

Characters

You know these folks. They’re the heroes, the sidekicks, the villains, and bystanders. When we’re thinking about stealing a story for our table, the characters in your target story are important, but a lot less so than you might think. That’s because your players should be the main characters, but you can’t expect your players to make the same choices those characters did.

And that’s a good thing.

If you expect your infernal pact warlock to hide their contract from the party the way Rumi hides her demonic heritage from the other members of HUNTR/X, then you’re making some huge assumptions about your players and taking away a lot of their agency.

So what will this ingredient be good for? NPCs, of course. Especially villains. Hell, you can twist it around so your players end up fighting the world’s favorite supernatural idol group.

Situation

You may be tempted to call this “the plot,” but I want to veer away from that word because plot and story tend to be synonyms in most people’s minds. I don’t want us prescribing the route our players will take through the adventure.

Instead, think of the situation as the context for the action. It’s all of the various external events that bring the players together and propel them towards the climax.

For example, if we say, “a demonic boy band is using their music to steal the souls of their fans,” we’re giving our players context for the situation without dictating how they should solve it.

Depending on the length of the story you’re stealing, the characters could find themselves in a lot of different situations. Make note of them, and save them for our synthesis phase (coming up shortly).

Goals

When you’re analyzing your story, look at the characters’ goals — what they want. Rumi, for example, wants to energize the Honmoon so she can banish all of the demons in the world and live a normal life.

Ideally, your players’ goals should be determined by the players themselves, but the more you train your brain to think about the goals of the characters within your favorite stories, the easier it will be for you to pull out the appropriate elements. Then, when your paladin player comes to you with a tragic backstory and says, “My paladin is hunting her father, who betrayed his knightly order and brought shame to my character’s family,” you’ll know where you can situate that character within the rest of the story.

A traitorous father is not the same as a secret shame, but it’s close enough that you’ll know what to do when the time comes. And by that, I mean…

Obstacles

Now we’re getting into the real meat and potatoes of what it means to steal a story. Obstacles are the things that get in the way of the characters from achieving their goals. A demonic love interest, for example, forces a character to realize there are shades of gray in a world she once thought of as black and white. Or having your secret shame outed in front of a room of people you’ve been lying to for years. These are the roadblocks that create delicious, delicious conflict. The kind that keeps our players on the edges of their seats, wondering how they’re going to get out of this one.

When you combine the situation with character goals and obstacles, that’s where the “plot” develops. Where the story comes to life. And studying the kinds of roadblocks your favorite stories throw in the path of their protagonists will help you port those obstacles into your campaigns.

Your Favorite Thing

Maybe it’s a derpy demon tiger. Or themes of found family and self-discovery. Or really cool outfits. Make note of your favorite thing(s) in your favorite stories. It doesn’t have to be big and important — like the way all of the Saiyans are named after vegetables in Dragon Ball Z — but it can be a big thing too — warp technology in Star Trek.

I want you to note your favorite things for a couple of reasons, but mostly because they’re the elements that draw you back into the story. So, regardless of how important the tiger is to the plot, it’s important to your heart. And if you can find ways to incorporate Derpy into your campaign, well, that’ll give you even more investment, and your excitement will spill over into your players, creating a wonderful feedback loop of awesome.

Take this list and go through three or four of your favorite stories, making the notes I mentioned above.

Once you’ve done that, come back here because…

IT’S TIME TO GET WILD

Now that you’ve got a stack of notes about characters and goals and giant blue tigers, it’s time to start synthesizing them and turning them into your next game session. How do you do that? Well, you pick up your elements like they were action figures in a toy chest, and you smash ’em together and make ’em kiss.

This technique works best when you mash up two stories from different genres. Take my “Hannah Montana/Buffy the Vampire Slayer” joke above. From Hannah Montana, we’re taking elements of musical acts and the pull between two lives — one very public and one very private — and we’re mixing that up with the supernatural demon slaying from Buffy.

What happens if you mix up Star Wars with Downton Abbey? Or Edgerunners with Fraggle Rock?

I don’t know, but it sounds like fun! And when you’ve broken down your stories into their elemental components, you get to find out.

Use the goals and the situations to create hooks. Then lean on the obstacles to create your encounters. Sprinkle in NPCs from the characters you’ve studied and bam! Your campaign is ready to rumble. Just add players and chase your favorite things through the new story you totally didn’t steal.

THE CONCEIT

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve probably figured out that I’m not really talking about heisting a story like it’s a diamond in a vault. I’m talking inspiration. Where we find it. How we call on it. And most importantly, how we can teach our brains to find it even when we’re not feeling inspired.

The more we study stories and how they work, the easier it will be to come up with our own. Original or not, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that we love them, even a little, and that our players are having fun.

What are the wildest mashup ideas you can think of? Leave them in the comments and let’s figure out how to turn them into campaigns!

Gnomecast 222 – Combating Analysis Paralysis 8 Oct 3:00 AM (14 days ago)

Join Ang along with Jared and JT as they talk about how to combat analysis paralysis! What do you do when your players get stuck overthinking and overanalyzing things and start dragging the game down! Links:

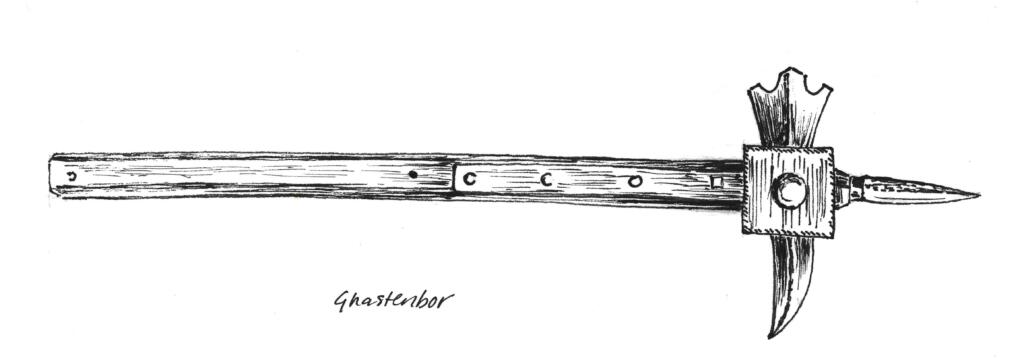

Making Weapons More Interesting 3 Oct 3:00 AM (19 days ago)

You don’t need me to tell you there are A LOT of RPGs out there. There is a huge, diverse, and wildly creative selection to choose from. Just counting those that involve medieval (ish) combat, this is still true. But despite the huge variety of mechanics, trends in modern game design, and dramatic reimagining of these games, there is one mechanic that is remarkably consistent: variable dice damage for weapons.

All d20 systems, as far as I know, but also percentile systems and a whole slew of other games, use different damage dice for different weapons and nothing else. That’s all you get to distinguish a short sword from a lance. And that’s not a problem if you want your combat abstracted and you like what you know. You might be perfectly happy that nobody ever uses a spear in your games, even though they were the most used weapon for thousands of years. Or that the half dozen or so blunt weapons in your game are all but redundant, bar fighting undead. Apart from the fact that I find it fundamentally unconvincing that a blow from a short sword would hurt less than a blow from a long one, should it strike me, there is an intrinsic disadvantage to variable dice. It doesn’t take long for the modifiers your player characters get to outweigh the difference between those die types. The difference in the medium results of a d6 and a d8 is only 1 (3.5 and 4.5 respectively). Your d8 wielding player character only benefits from his choice of weapon one in four die rolls (I know I’m simplifying the laws of probability here, but you get the gist…). And once other rules kick in, especially with level-based progression, that 1 to 2 points of damage soon vanishes beneath the avalanche of bonuses, additional damage dice, magic weapons, or increased Attributes.

Soon enough, the weapons are just flavour. Which is fine. I guess.

But to me it seems a wasted opportunity. In 2014, 5e introduced Qualities to its weapons. It wasn’t the first system to use the idea, and they mainly took the place of pre-existing rules. Still, they added some interest, but they were fairly limited. They didn’t change the way players thought about their characters’ weapons. I am well aware that most people don’t want to bog down their combat with complex rules, cross-referencing weapon types with armours, as I tried to do with homebrew rules back when I was young and foolish and didn’t know better. But Reach and what a weapon does on a critical success, can easily make combat more interesting. And fun!

In fact, in many ways, the other stuff can do more to distinguish one weapon from another, more to add flavour to the fight, more to make your character stand out, and more to make a fight, well, interesting, than different-shaped dice. Ever get the feeling that some (or all?) of your players are ‘tuning out’ when it isn’t their turn in combat? That might be because it’s predictable. And I mean that the process of resolving combat has become predictable, not just the outcome. Think about it: most of these sorts of games, whether d20 based or not, generally tend towards the ‘roll dice, add modifiers, hit a target number, roll damage, modify, end’. Sometimes there is an option to parry, or to dodge, or you might compare scores, like in Runequest, to see the outcome. But it matters little whether you’re swinging a longsword or a war hammer. The weapon you are using is unlikely to alter the outcome of the fight, other than its duration. Not really.

So, what can we do about it?

First off, let’s think about Reach.

Weapons vary a lot in length. If you know what you’re doing with one, that can really impact how easy or difficult it is to strike your opponent or, more importantly, for them to strike you. I got some first-hand experience of this when my son was little, and we fenced with garden canes. Yeah, cute, right? Until he picked up the garden hoe and I realised I was in trouble! Because it is incredibly difficult to ‘parry’ a long, sharp, stabby thing with a one-handed, short, stabby thing (or slashy or bashy thing), unless you have a big round woody thing. Even if you stop them hitting you, you have to get past that to hit them. Sure, a swordsperson could get past a spear-wielder and strike, if they are nimble, I hear you say. Well yes… maybe that should be part of the game?

Axes are often portrayed as particularly destructive in RPG combat systems. They have a tendency to sever things…

Modiphius’ “Conan: Adventures In An Age Undreamed” (2016, now out of print) used Reach scores of 1 to 4, assigned individually to weapons. Where Reach scores differed, the lower was subtracted from the higher and the difference became a disadvantage to the wielder of the shorter weapon. When I ported this rule to a d20 game, I assigned scores of 1 to 5, because that way, I could easily give a score of 5 to weapons already listed as having Reach. After play-testing, only a Pike would ever get Reach 5 in practice.

If a Pike has Reach 5 and bare hands have a Reach of 0, you can pretty well fit other weapons to the scale: dagger and short sword have Reach 1, normal sword Reach 2, bastard sword Reach 3, two-hander Reach 4. You can work out most weapons from that kind of scale.

In practice, you immediately start seeing the humble spear getting picked up a lot more, with its Reach 4. In a game I ran recently, two stalwart adherents to the axe and shield model suddenly realised my NPC guards were getting a big advantage from the reach their spears gave them. As soon as they (eventually) dispatched them, they snatched up those spears like they were yreasure! Which, of course, they were…

Weapon Qualities are another thing altogether. Dungeons & Dragons 3.5, which had its issues, varied the Critical Threat range of its weapons, which was fun. Swords all critted on 19-20 but axes had a crit damage multiplier of 3. Nice. But another way to distinguish weapons entirely is to label each weapon with a single one-word descriptor of what it is good at and use existing rules to resolve critical hits. For example – ‘Thrown’, which most systems will already use. If war hammers and mauls have the ‘Knockdown’ quality, which results in the victim being knocked Prone, suddenly new opportunities open up for how a fight might evolve or end. Whether you still multiply damage or not is up you or your table. ‘Stun’ is another obvious one – but not just for rogues knocking out guards; being stunned in most rulesets makes you an easy target for a potentially killing blow, maybe even a coup de grace, or else prevents you from attacking. Perhaps in your game a ‘stunned’ target takes a penalty to their armour or defence score?

I recommend you try this out in your own game and see what happens. Don’t worry about trying to introduce too many Qualities at once. You only really need to assign Qualities to the weapons your player characters have and to those most popular with NPCs. Let your players get used to a couple first. Make sure you don’t stack too many qualities in a single weapon: it will soon become the only one players use.

Here are some examples of Qualities I have used:

- A ‘Savage’ weapon automatically inflicts more damage. How much depends on your system – perhaps an additional hit point or hit die.

- ‘Mounted’ might get a bonus to hit and to damage when used from horseback; lances or scimitars might have this.

- ‘Brutal’ might get an increase in critical multiplier or automatically score maximum damage or get a bonus when rolling on the critical table.

- ‘Armour Piercing’ reduces the effectiveness of armour – either the Armour Class or the amount damage is reduced by. The infamous ‘bollock dagger’ of the Middle Ages was designed to fit through the gaps in plate armour.

- ‘Parrying’ can be applied to daggers, maybe, or swords, giving a bonus to the parry skill or an additional parry attempt per turn, or simply add to a defensive score such as Armour Class.

- ‘Cover’ might be a quality given to shields, which enables them to parry arrows – allowing an attempt to avoid the hit entirely instead of increasing an armour score or just reducing the damage.

- ‘Fearful’ weapons are intimidating and require a Will save or equivalent, to not take a small to hit penalty due to being intimidated.

The best Qualities are the ones that require the player character to do something in order to take effect. The ‘Ruthless’ quality (perhaps attached to certain daggers or a crossbow) might mean that if the player character spends a round eyeing up the target by making the equivalent of a Perception/Observation/Spot check, then the weapon gains other qualities – maybe ‘Brutal’ or ‘Savage’ or both, from above. But only if you make the skill test to spot the gaps in their armour or the patterns in their movement.

Qualities and Reach should be about encouraging players to engage with their characters’ weapons and enabling them to do more than just ‘roll to hit’ time after time.

They are about putting a fork in the road of the combat, making outcomes less predictable and letting different characters shine in different ways.

As with anything, try it out and see how it works at your table.

Basic Elements of NPCs 29 Sep 2:00 AM (23 days ago)

NPCs in your RPGs come in all shapes, sizes, purposes, abilities, and reasons. It’s near impossible to enumerate all of the facets of an NPC or why they are in the storyline. Despite the Herculean task before me, I’ve done my best to outline what I think are the basic elements of NPCs in your games.

Purpose: Provide Information (Rumors/Clues)

NPCs can provide information to the PCs. This information can be true or false, somewhere in-between, or a little of both. It can be helpful, sidetracking, direct, or indirect. The NPC might actually know things that can help the party. On the other hand, the NPC might have heard from his cousin’s best friend’s ex-girlfriend’s former roommate that something is going down on Elm Street at night. These kinds of rumors need to be couched as such instead of having them being presented as full truths. The exception to this is if the NPC absolutely believes in the truth of what they are saying.

One the point of providing information that sidetracks the PCs, this might fall into the category of a “red herring” depending on how the information is delivered and if the PCs can detect if the NPC is trying to intentionally deflect the party from the main goal or mission. Tread carefully with information that will intentionally throw the party off the main trail, especially if it will take a long time to resolve the sidetracked nature of the information.

Purpose: Provide Support

NPCs can also be supportive to the party. This could be as simple as a shopkeeper staying open late to allow the PCs to reequip at the last second before delving back into the Forest of Tears as the sun goes down. The support can also be monetary or with aid from other NPCs. Factions go a long way into playing into a support structure for the PCs.

NPCs can also provide non-monetary support in the form of favors asked, owed, or due. This could be free henchmen/hirelings, cheap mercenaries, the loan of a powerful item, free/cheap healing potions, or a handy map that will lead them down the safest path through the Forest of Tears to reach the Necromancer’s Citadel in the heart of the forest.

Purpose: Provide Inspiration

Rah! Rah! Rah! You can do it!

No. Not that kind of inspiration… kinda.

What I’m talking about here is to give the PCs motivation to go forth and be the Big Darn Heroes of the story. This can be a quest giver, a mission handler, a faction leader, or someone else that will put the party on the path to greatness. These don’t always have to be people in positions of power. The lonely orphan on the street begging for loose change so he can pay for a cure disease spell to help out his headmaster can inspire the party to delve into the orphanage to cure the headmaster, and/or find out what dire events are plaguing the orphanage.

Purpose: Provide Opposition

NPCs can also oppose the efforts of the party. This is usually in the form of minions, lieutenants, bosses, the BBEG, monsters in the way, and other things that can result in combat. This doesn’t always have to be the case, though. It could be that the old lady in the back of the tavern is the bandit captain’s mother. She might not be proud of her son, but she doesn’t want to see him dead at the tip of a PC’s sword, either. She might misdirect the party or sabotage their equipment while they drink it up or sleep it off.

Purpose: Fill in the World

Lastly, there are more non-important people in the world than important people. At least, this is true of storytelling efforts. Each person is the hero of their own story, but you’re only telling the story of the players’ heroes. If an NPC doesn’t fulfill an important role, they fill the world with their presence. This will make your world, setting, tavern scene, or street movements feel authentic by having people present. They don’t need to be named or detailed or even given descriptions, but they still need to be mentioned as being there. A street devoid of people is an oddity that the PCs might get interested in… even if you don’t want them to.

Features: Notable Appearance Details

Give each important NPC two or three appearance details. Clothing, facial hair, hair style, jewelry, level of cleanliness, smells, and so on are important to keep your NPCs memorable in the minds of the players and important to the attention of the characters. This is one reason the “affectation” chart in Cyberpunk 2020 is so incredibly potent. I just wish the list were longer, so there would be fewer repeats. The solo with the cybershades and three interface ports on his forehead is more memorable than the rockerboy with a chromed guitar. Though (and this is from one of my CP2020 games from ages ago), a rockerboy in full chromed-out, hardened body armor is certainly memorable, especially while on stage under all those lights.

Features: Personality Quirks

Give your NPCs a quirk. Maybe they don’t make eye contact, or they make intense eye contact at all times. Maybe they don’t blink much at all. Always smiling is another good trait. Then again, so is never smiling. Popping knuckles is a good one. Maybe the NPC has a phobia or hates the taste of ale or has zero-g sickness. Pick an appropriate quirk for your setting and apply it to your NPC.

I recommend only one quirk per NPC, and I only recommend spending your time coming up with that quirk if the named NPC is going to directly interact with the party or intersect with the story arc in some manner.

Features: Accents/Speech Patterns

I can’t do accents. Period. Full stop. I don’t even try. If you can pull off accents, go for it! Yay! Though, not everyone is going to have that “odd” accent, so don’t overdo it. You might find yourself using the wrong accent for the wrong NPC or driving the players batty trying to remember which NPC had which accent.

I fall back to using speech patterns. Rapid-fire speech. Run-on sentences are good (especially if from the mouths of young children). Fragments getting used all the time. Delayed or hesitant speech. A long, thoughtful pause before answering a question or delving into a conversation. Using lots of contractions… or none at all. Another good one to use is someone saying, “umm” or “errr” or “hrmm” before each paragraph like they’re trying to piece together what they want to say. Applying a stutter to an NPC’s speech pattern will call them out as being memorable as well.

As an example, I had a great uncle who would start every affirmative statement with, “Yep, yep, yep.” He would also start every negative statement with, “Nope, nope, nope.” This happened without fault, and I found it quite endearing. My grandfather, however, found it annoying. Regardless of how we perceived my uncle’s speech trait, it was memorable.

Features: Goals

Everyone has goals. Period. Full stop.

It could be to turn a coin or make a buck by the end of the day to pay for rent. That’s minor, applies to almost everyone, and is important, but it’s also a goal. The goal could be to conquer the neighboring nation, or as personal as finding their lost cat.

Each NPC that impacts the story (meaning just a handful of them) or has an important encounter with the PCs needs to have at least one goal in mind for their interactions. The more important NPCs could have as many as three goals. Yep. Three of them.

I learned from the great author, Kevin Ikenberry, that important characters in a story should have a professional, personal, and private goal. Each of those are subtly different and may have some overlap in them. The professional goal is how the NPC is going advance their position in their job, society, faction, or similar arenas. The personal goal is what the NPC holds dear in their heart to cross off their bucket list before the last day comes for them. The private goal is one they attempt to accomplish, but will never tell another soul about.

Features: Motivations

Each goal must have a motivation attached to it. Just trying to accomplish something is hollow. It doesn’t ring true. There are motivations behind every goal, so when you attach a goal to an NPC, you need to attach a motivation to that goal. Just ruling the world for the sake of ruling the world creates a “mustache-twirling evil person,” and you want something deeper than that to drive your plot, your story, and your PCs into action.

Features: Secrets

Most people have secrets. Not all of them will impact your party or the story you’re telling. If that’s the case, don’t worry about generating a secret for the NPC. However, if the NPC secretly supports the bandit captain (see the mother example above), then that’s probably going to be kept secret by the NPC.

If the secret never comes out in front of the PCs, that’s okay. It doesn’t need to. However, if it doesn’t, then it must drive the NPC’s actions, reactions, goals, and motivations. This indirect influence on the NPC will make the NPC feel more authentic and three-dimensional.

Conclusion

What did I miss? Are there any other facets of NPCs that you feel are important? Let us know!

What’s Your Pre-Game? 26 Sep 2:26 AM (26 days ago)

Every week, I run a game on Sunday evenings. Currently, I am running Blades in the Dark and Neon City Blues on alternating weeks. Every Sunday afternoon, I start my pre-game so that I am ready for game night. What makes up my pre-game changes depending on the game, where it is being played, etc, but there is always a pre-game. Let me tell you about it.

Getting Ready to Play

I try to be very organized in my gaming. Some of it comes from genetics, some from childhood trauma, and a bit comes from my time as a college DJ, where it was impressed upon me that you never have dead air. Never. I try to carry that through to my gaming by making sure everything is prepared.

Now in the prep life-cycle, pre-game is the second-to-last step. The first steps involve session and campaign prep. I talk about those a lot in Never Unprepared and with Walt in Odyssey. The last step is mise en place, when you set up your gaming space.

Back to pre-game. It is your final chance to get things in order so that you can come to the table ready to play.

Things to Consider

There are two components to pre-game: mental and physical.

The Mental

The mental part of pre-game is to get your mind ready to run the game. For me, this is the time when I take a final look at my session prep and start loading it into short-term memory. I have prepped the game some time before Sunday, typically at the start of the week, so I don’t always remember every detail of what I came up with. With the game only hours away, it’s now safe to put all the details into my short-term memory.

That is accomplished by reading my session prep and imagining how various scenes will look, or how NPCs will sound. Based on this, I may add a few last-minute notes to my prep.

I will also use this time to check any notes (mine or the players) on the past session to also refresh myself on what happened at the last session.

Finally, this is the time to check any rules that may come up or just browse the rule book to reinforce the mechanics of the game. For newer games, this may be sitting down and re-reading the rules; for games I am more familiar with, it could be just looking up some specific rules, powers, or spells that are going to come up.

The Physical

On the physical side, this is the time to get the physical components together for the game. Depending on whether your game is at your place or another place, this will vary. If you are playing at your place, this may also be a time to prepare your physical gaming space, cleaning or tidying up. If you are playing online, this is the time to prepare your VTT.

Here are several possible activities you may need to do, depending on where your game is played and what game is being played. This list isn’t comprehensive, I am sure you can think of a few more things…

- Cleaning and preparing the gaming space

- Deciding what books you will need at the table

- Gathering minis or making tokens for the encounters planned in the session

- Getting together maps (physical or digital) for the session

- Printing handouts

- Gathering props to be used in the game

- Packing your gaming materials for transport

- Uploading assets to your VTT

- Determining what aids you need for the game (cards, name lists, etc)

- Charging electronics (tablets, laptops)

- Making a playlist or loading a soundboard for the session

Pro-tip: If you are using any electronics, run updates during your pre-game. Nothing kills the flow of a game like a device that starts to update when you get to the table. During pre-game, check for updates and run them while your devices are charging.

My Game Day Rituals

For both my games, my session is on Sunday evenings, so my pre-game happens early Sunday afternoon. It is just a few hours before the game, so I have ample time to run through all the items on the list without feeling rushed.

For my Blades game, I am running at a friend’s house. So my pre-game looks like this:

- Read the session notes – load into short-term memory.

- Optional – re-read parts of the rulebook.

- Charge my iPad and Apple Pencil.

- Confirm the sync of my Obsidian database from my desktop to my iPad.

- Confirm the sync of my OneNote session notes from my desktop to my iPad.

- Set up session notes pages in my Blades Good Notes notebook, and put a heading and page number on them.

- Gather my physical materials – Character sheets, rule book, Clock Cards, etc.

- Pack my game bag.

For my Neon City Blues game, my pre-game looks like this:

- Clear my dining room table.

- Read the session notes – load into short-term memory.

- Review the open mysteries.

- Charge my iPad and Apple Pencil.

- Confirm the sync of my Obsidian database from my desktop to my iPad.

- Confirm the sync of my OneNote session notes from my desktop to my iPad.

- Set up session notes pages in my NCB Good Notes notebook, and put a heading and page number on them.

- Gather my physical materials – Character sheets, rule book, Clock Cards, etc.

- Put everything on my rolling cart in the office (it gets rolled out to the dining room table after we eat).

Preparing for Success

The pre-game is an important step in being prepared to run your session. It gets you organized mentally and physically to come to the table and run a great game. What goes into your pre-game will be a mix of your style, the game you are playing, and where you are playing. Come up with a pre-game (and even make it a checklist if you need to), and you will be prepared to run your session.

Also, one last time — run your updates before your session starts!

Do you pre-game? When do you do it? What is in your pre-game?

Gnomecast 221 – Fixating on Trifles 24 Sep 3:00 AM (28 days ago)

Join Ang, Chris and JT as they chat about what to do when your players get fixated on trifling matters that you didn’t intend to matter in the game. Do you make it matter or do you redirect them, and how do you do either of them?!?

LINKS:

The Streets of Avalon Playtest

Gnomecast 220 – Virtual vs. In-Person 10 Sep 3:00 AM (last month)

Join Ang along with Josh and Jared as they talk about the pros and cons of playing virtually online versus playing in person face-to-face. Listen to them talk about what they love about both ways of playing!

LINKS:

Coyote & Crow Digital Kickstarter